If you believe the headlines, robots aren’t just coming for your job—they’re already in the breakroom. From AI replacing copywriters to algorithms designing logos and even writing music, entire industries are bracing for a future where human labor may no longer be needed.

In Hollywood, striking actors and screenwriters have called out AI for threatening to digitize their work without fair compensation.

It’s a tale as old as innovation itself: every new machine disrupts the workplace, leaving people to wonder—will there still be a seat for us at the table?

For musicians in the 1930s, that dystopian future wasn’t a headline—it was already here. The rise of “talkies” and prerecorded music in theaters led to mass layoffs, as live orchestras were replaced by machines spinning reels of “canned music.”

In 1930, the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) took a stand. Armed with $500,000 and an arsenal of arresting advertisement, it formed the Music Defense League (MDL) and launched a campaign to fight back against the mechanization of art.

Their message was clear: machines weren’t just taking jobs—they were draining the very soul from music itself.

The Golden Age of Theater Orchestras

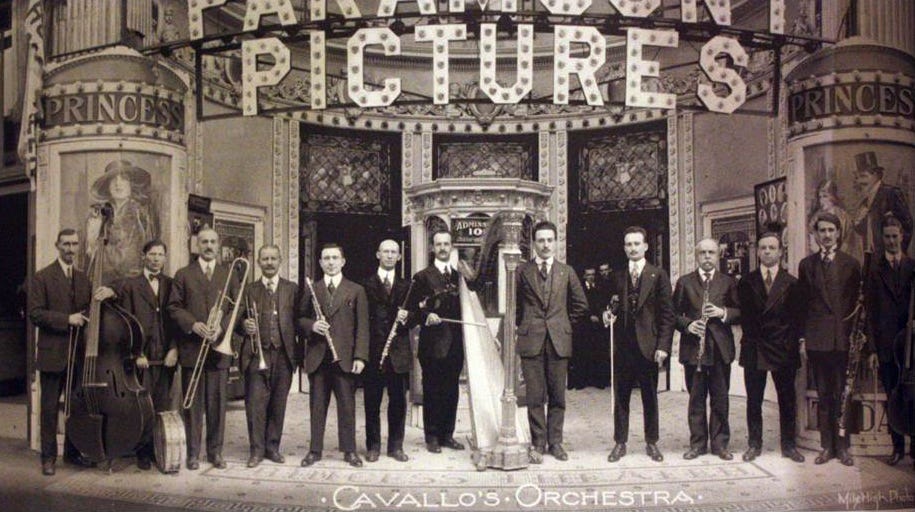

In the mid-1920s, live music wasn’t just part of the moviegoing experience—it was the heartbeat of it. By 1926, 22,000 musicians filled theater pits across the country, representing a staggering one-fifth of the AFM’s membership.

Theaters ranged from modest neighborhood venues with a lone organist to opulent “movie palaces” like New York’s Roxy Theatre, where the spectacle included a 110-piece orchestra, a three-consoled Kimball organ, and a dedicated sound effects team.

These weren’t just films—they were immersive events designed to dazzle every sense.

One ad from the era captures this magic: a sprawling orchestra, instruments gleaming, performing in front of a towering movie screen. This was art as a spectacle.

Orchestras didn’t just accompany the film; they elevated it, crafting live soundscapes that brought silent movies to life and fully engaged the audience’s senses.

The Arrival of Talkies

Then came The Jazz Singer. Released in 1927, the first “talkie” didn’t just synchronize sound with the screen—it synchronized an entire industry to its technological future.

To put it in today’s dollars, theaters spent around $150,000 to $250,000 installing sound systems—but a bargain compared to the nearly $900,000 annually it cost to maintain a 15-piece orchestra.

For theater owners, the math was irresistible. Recorded soundtracks didn’t take breaks, demand union wages, or need overtime pay. Movies could run continuously, packing theaters and maximizing profits.

By 1930, weekly attendance soared from 50 million in 1926 to 90 million, proving that audiences were captivated by the novelty of synchronized sound.

But for musicians, this revolution was a death knell. The orchestras that had once elevated the moviegoing experience were now expendable, their artistry replaced by a cold, mechanical reel spinning the same notes night after night.

The Music Defense League Strikes Back

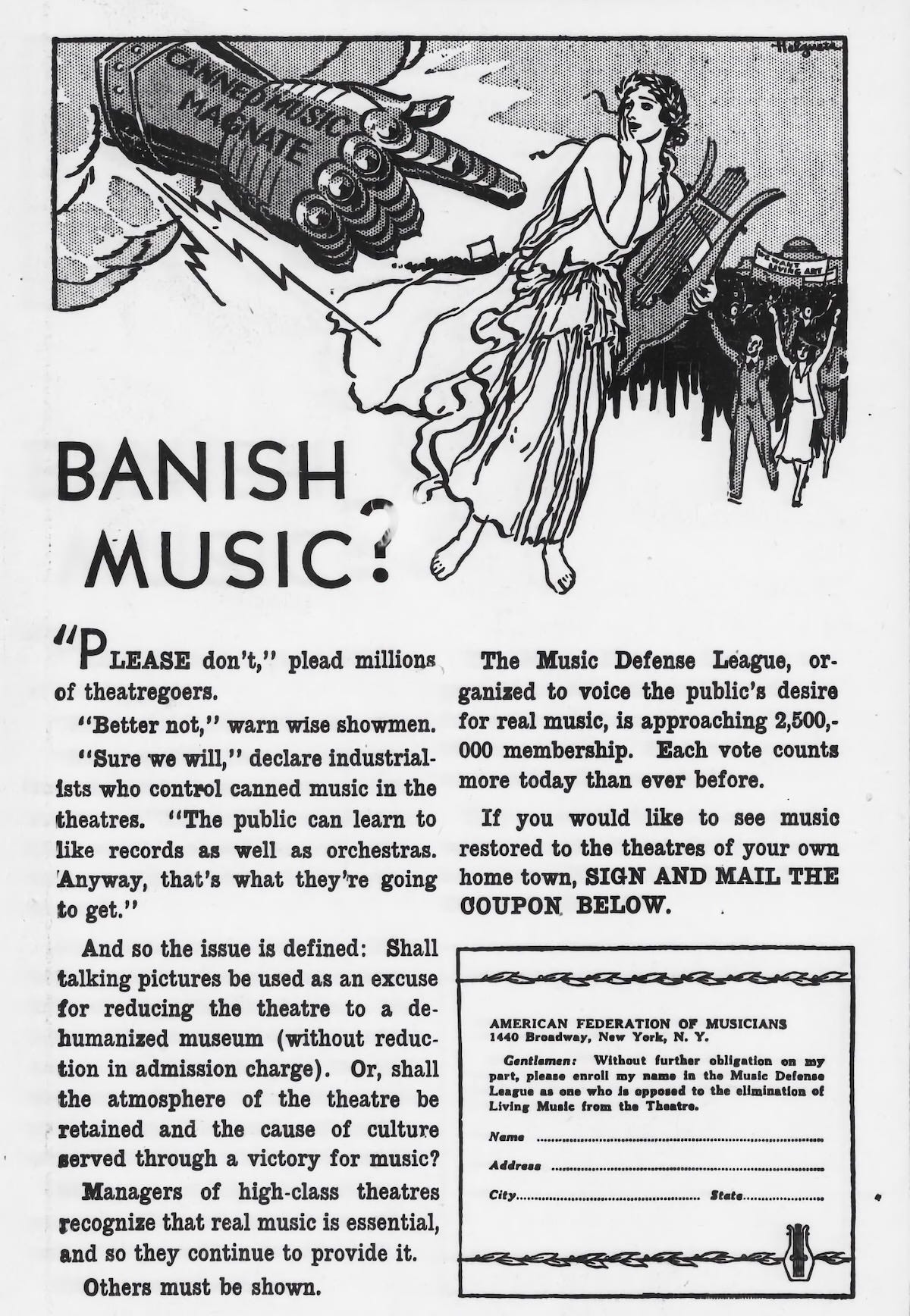

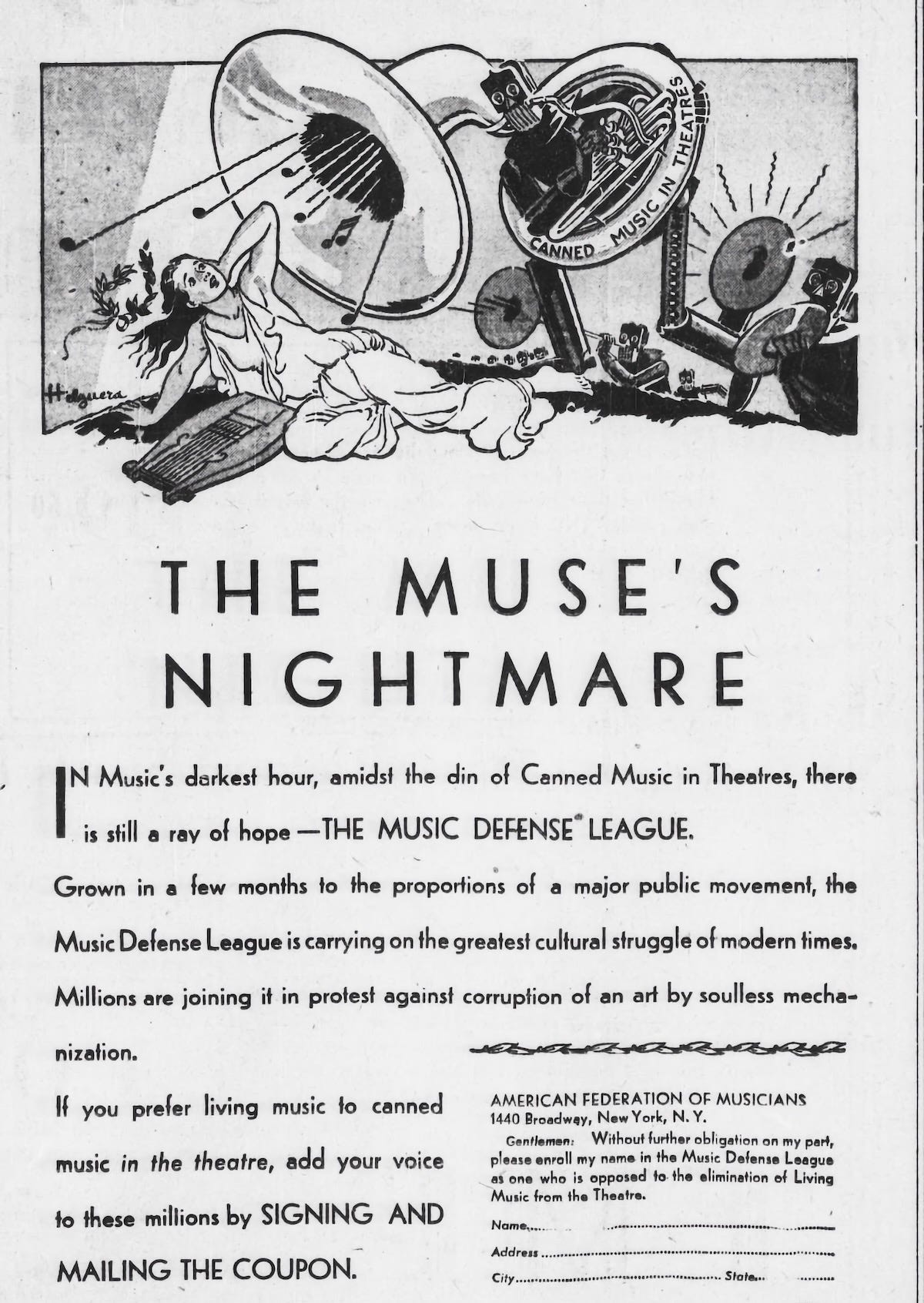

Faced with the existential threat of canned music, the American Federation of Musicians launched a counteroffensive in 1930: the Music Defense League.

Funded by a 2% tax on AFM members, the MDL declared war with one of the most dramatic public relations campaigns of its era.

Their rallying cry, splashed across newspapers, magazines, and billboards, was simple yet urgent: stop “Canned Music in Theaters.”

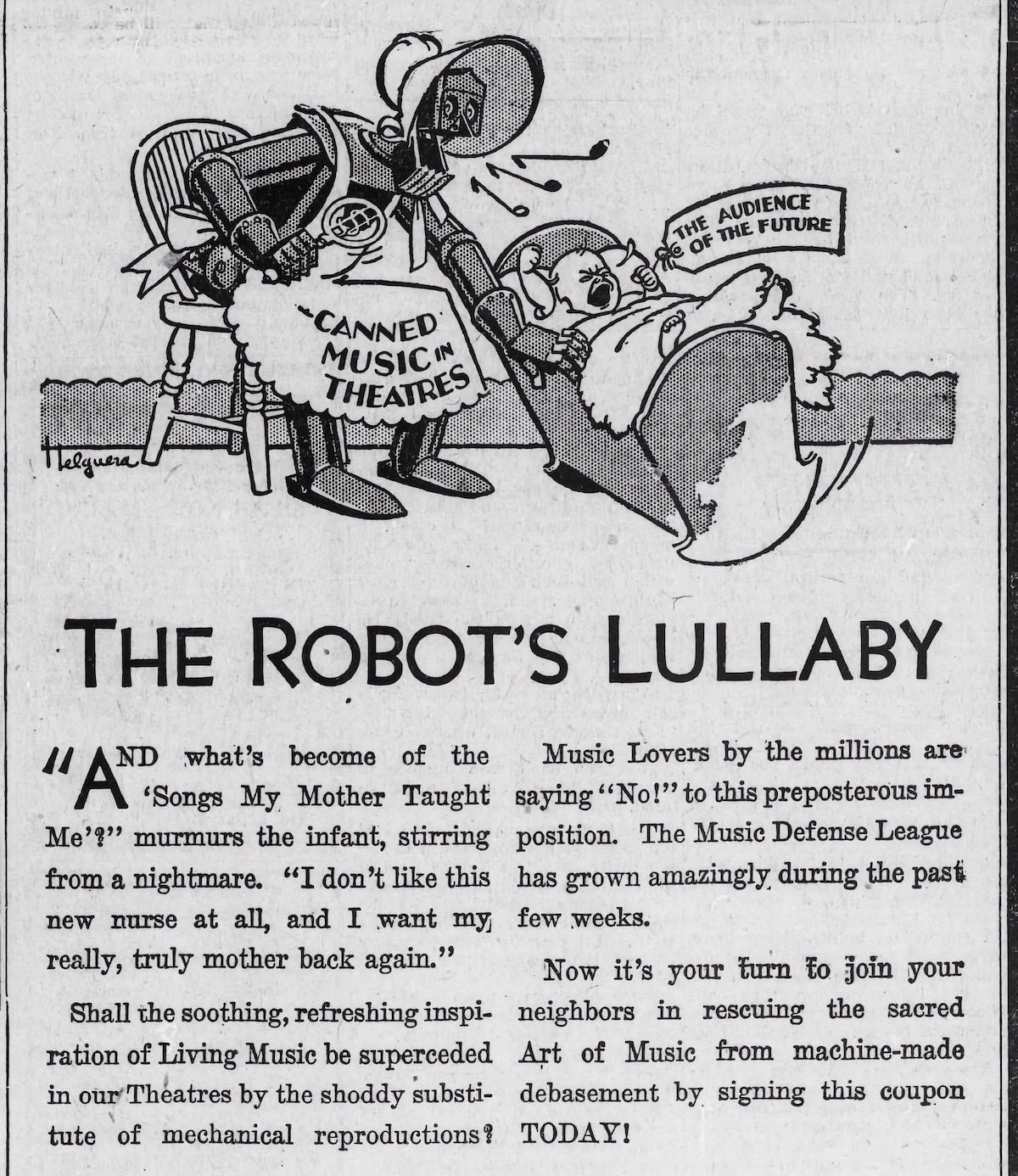

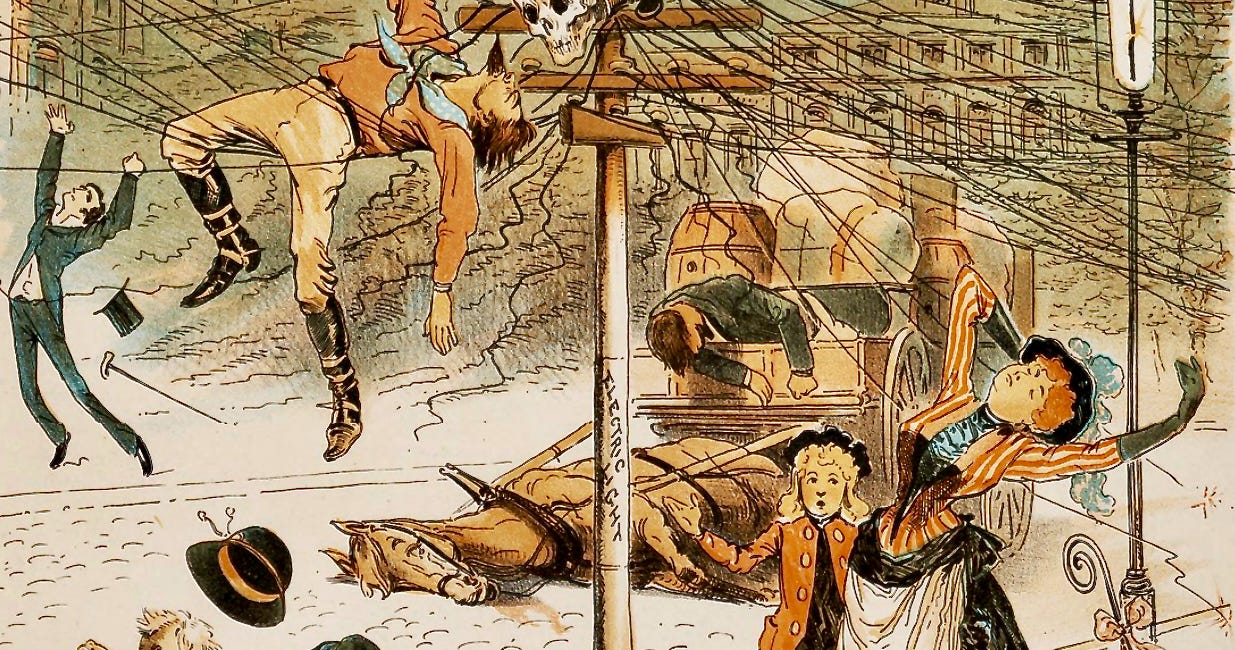

The visuals were nothing short of theatrical. One ad portrayed a towering robot crushing an orchestra and trampling over a terrified audience—a stark warning about mechanized art’s destruction of culture.

Another depicted a monstrous machine grinding orchestras into “musical mince meat,” as if turning creativity itself into something sterile and mass-produced.

Then there was the melancholy masterpiece: a somber tagline, “When Will That Young Man Go Home?”, paired with an image of a mechanical suitor awkwardly courting a disinterested muse. It was a cutting metaphor for the soullessness of canned music and a plea to preserve the human connection at the heart of art.

The End of an Era

Despite the Music Defense League’s bold campaign, their warnings and imagery couldn’t stop the tide of technological progress. By 1932, most theater orchestras had vanished, their soaring melodies replaced by the hum of film reels and prerecorded soundtracks.

For thousands of musicians, it was more than just a job lost—it was the silencing of a craft they had devoted their lives to. Some adapted, finding work in recording studios or pivoting to other industries, but for many, it marked the end of an era of artistry that could never be fully replicated.

The MDL ads captured a world at a crossroads, where the relentless march of progress came at the cost of culture, tradition, and the livelihoods of thousands.

Epilogue: The Sound of Progress

The Music Defense League’s campaign was more than a fight for jobs—it was a battle for the soul of art. To the AFM, live music wasn’t just entertainment; it was a connection, a shared human experience that no machine could replicate. Their message, woven into dramatic visuals and impassioned pleas, was clear: progress shouldn’t come at the cost of creativity.

Nearly a century later, their fears echo in the age of algorithms and automation. Today, AI isn’t just transforming industries—it’s taking up residence in the creative world.

Musicians face algorithms capable of composing symphonies in seconds. Writers compete with machines that churn out prose faster than a human can draft a sentence. Artists watch as software generates images with the click of a button.

The parallels are haunting. Just as canned music displaced theater orchestras, AI threatens to replace human creators.

And like the MDL, we’re left grappling with the same unsettling question: What happens when machines do the creating?

I was thinking about this yesterday! Our film club is covering David Lynch's Mulholland Drive this weekend, and I was thinking how cool it would be to hear Angelo Badalamenti's main theme played live during the movie. It's a wonderful orchestra piece, and when a good orchestra plays a good piece live, its audience gets the real deal in a way that simply is not otherwise possible...

Now I know why I never liked Kenny G.