Reading Percival Everett’s 2024 National Book Award Winner, James, was eye-opening. Everett reinvents Jim, the enslaved man from Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), as a deeply intelligent and resourceful character.

In James, Jim’s speech, like that of every black character in the novel, is a calculated code-switching put-on:

“White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them... The better they feel, the safer we are”,

or “Da mo’ betta dey feels, da mo’ safer we be”, in “the correct incorrect grammar” required by what Jim calls “situational translations.”

Early in the book, James shows a group of enslaved children how to use what he calls the “slave filter,” an exaggerated dialect meant to fool white people.

This scene highlights the careful performances James encourages as a way to endure and outwit those in power.

"You're walking down the street and you see that Mrs. Holiday's kitchen is on fire. ... How do you tell her?"

"Fire, fire," January said. "[T]hat's almost correct," [James] said.

"The youngest of [the children], five-year-old Rachel said, "Lawdy, missum! Looky dere."

"Perfect," [James] said. "Why is that correct?

Lizzie raised her hand. "Because we must let the whites be the ones who name the trouble. ...."

[Another child adds]: "Because they need to name everything."

This moment reveals a sharp irony: in public, enslaved people often performed exaggerated roles—bumbling, overly polite, or comically deferential—to appear harmless.

These performances weren’t just for show; they were calculated acts of survival in a world where stepping out of line could mean punishment—or worse.

Behind closed doors, though, Everett shows us the truth: sharp, strategic minds navigating their circumstances with remarkable care.

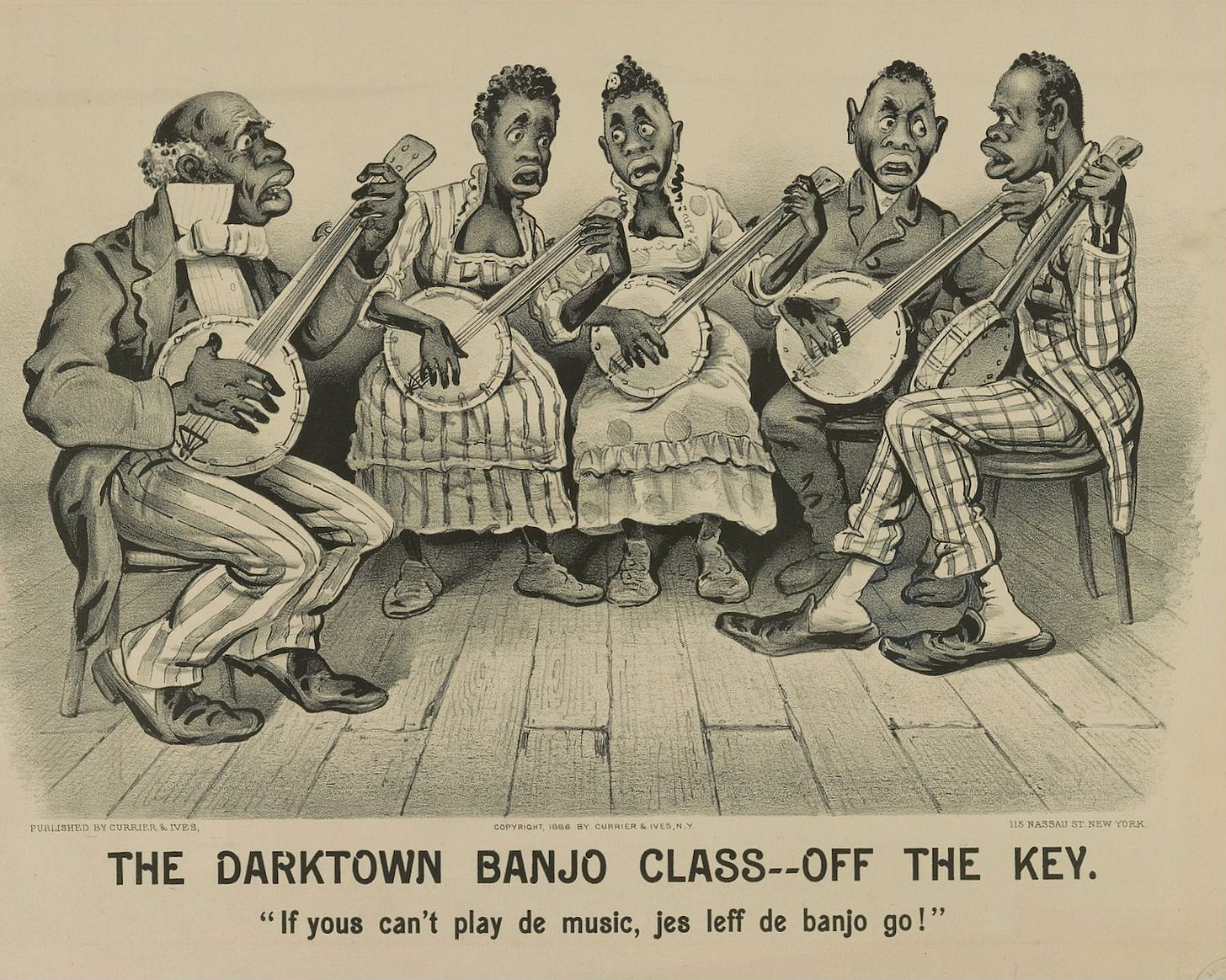

Everett’s James stands in stark contrast to the cartoonish depictions of Black life that dominated 19th-century popular culture, where lines like “If yous can’t play de music, jes leff de banjo go!” turned Black speech into a punchline.

These portrayals weren’t just cruel; they stripped language of its complexity and turned it into a weapon of ridicule. James, by contrast, wields language with precision—both as a shield and a tool of resistance.

Instead, he’s someone who reads Voltaire, understands the power dynamics around him, and wields language as both shield and weapon.

Here is James, finding himself in a white slaveowner’s library:

“I had wondered every time I sneaked in there what white people would do to a slave who had learned how to read. What would they do to a slave who had taught the other slaves to read? What would they do to a slave who knew what a hypotenuse was, what irony meant, how retribution was spelled?”

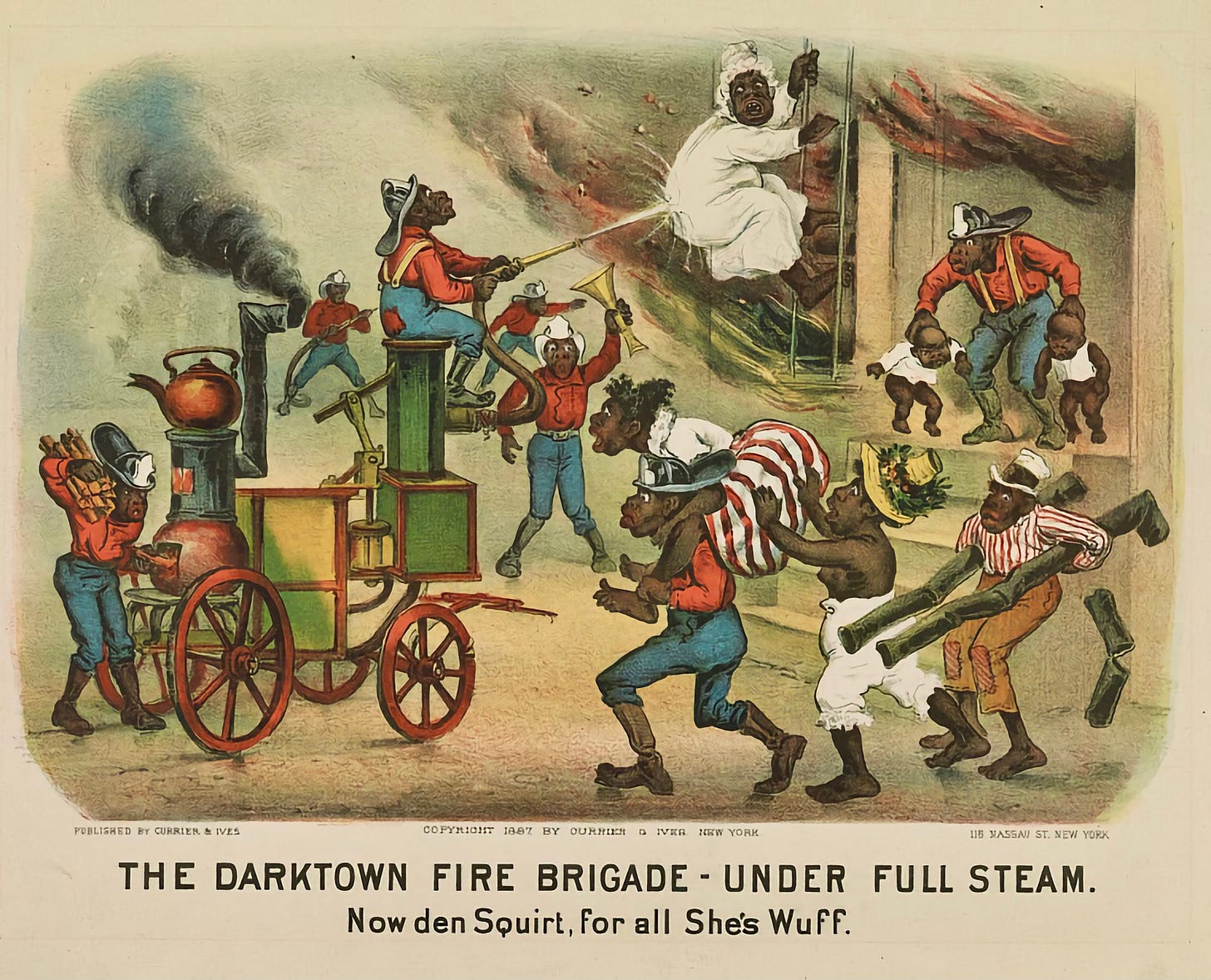

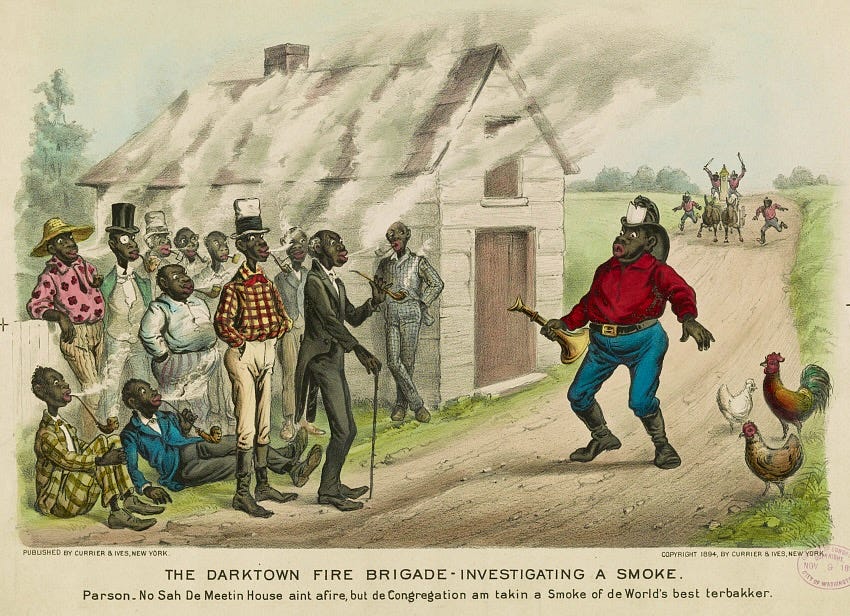

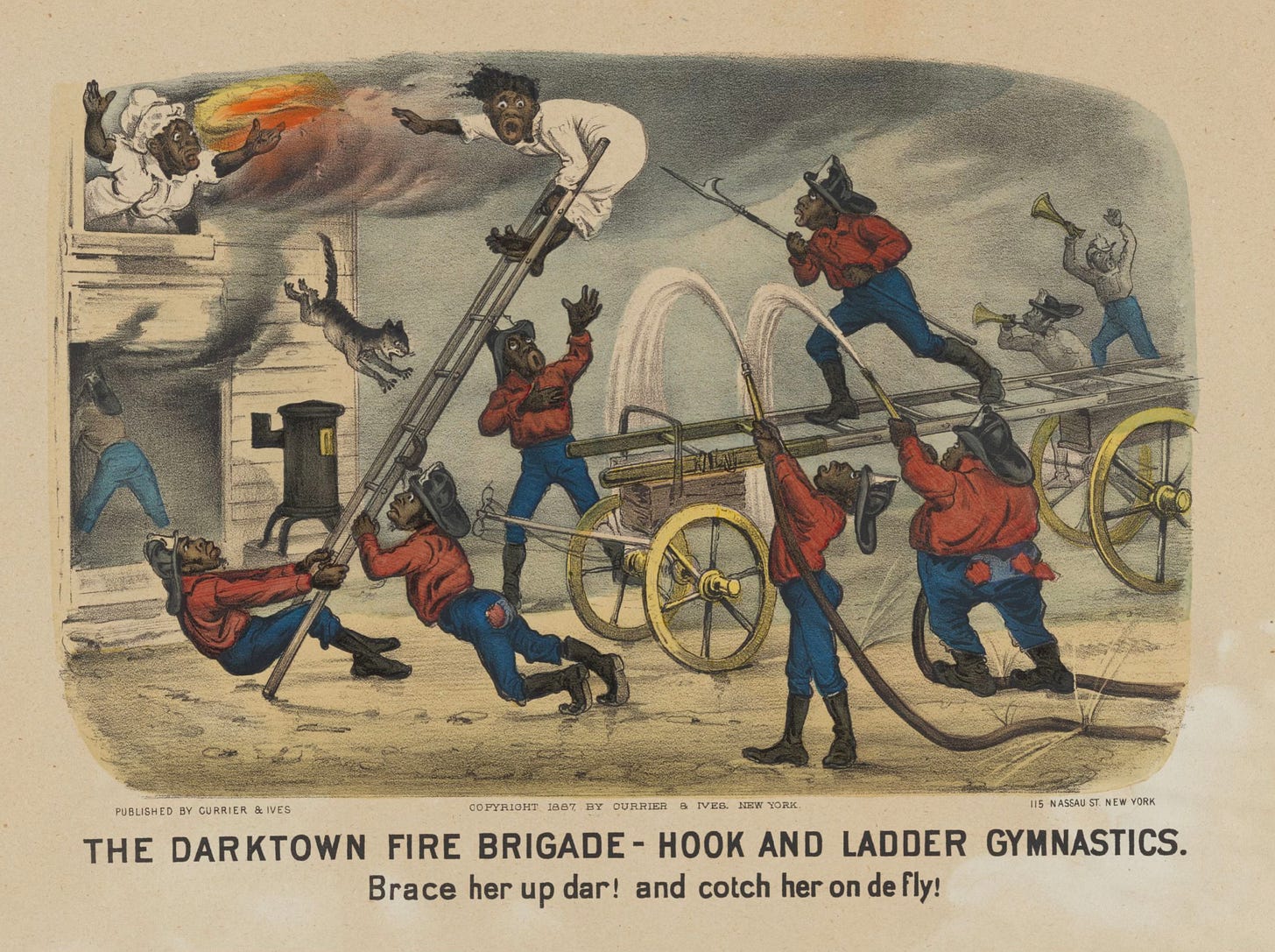

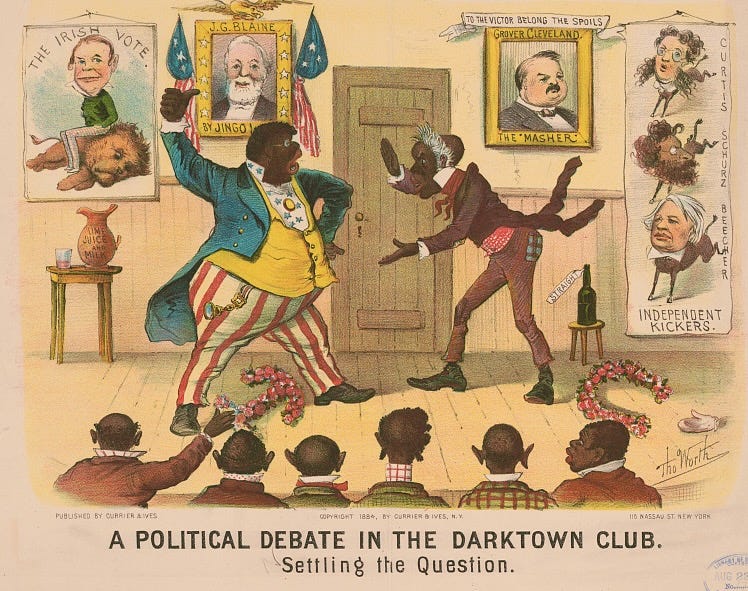

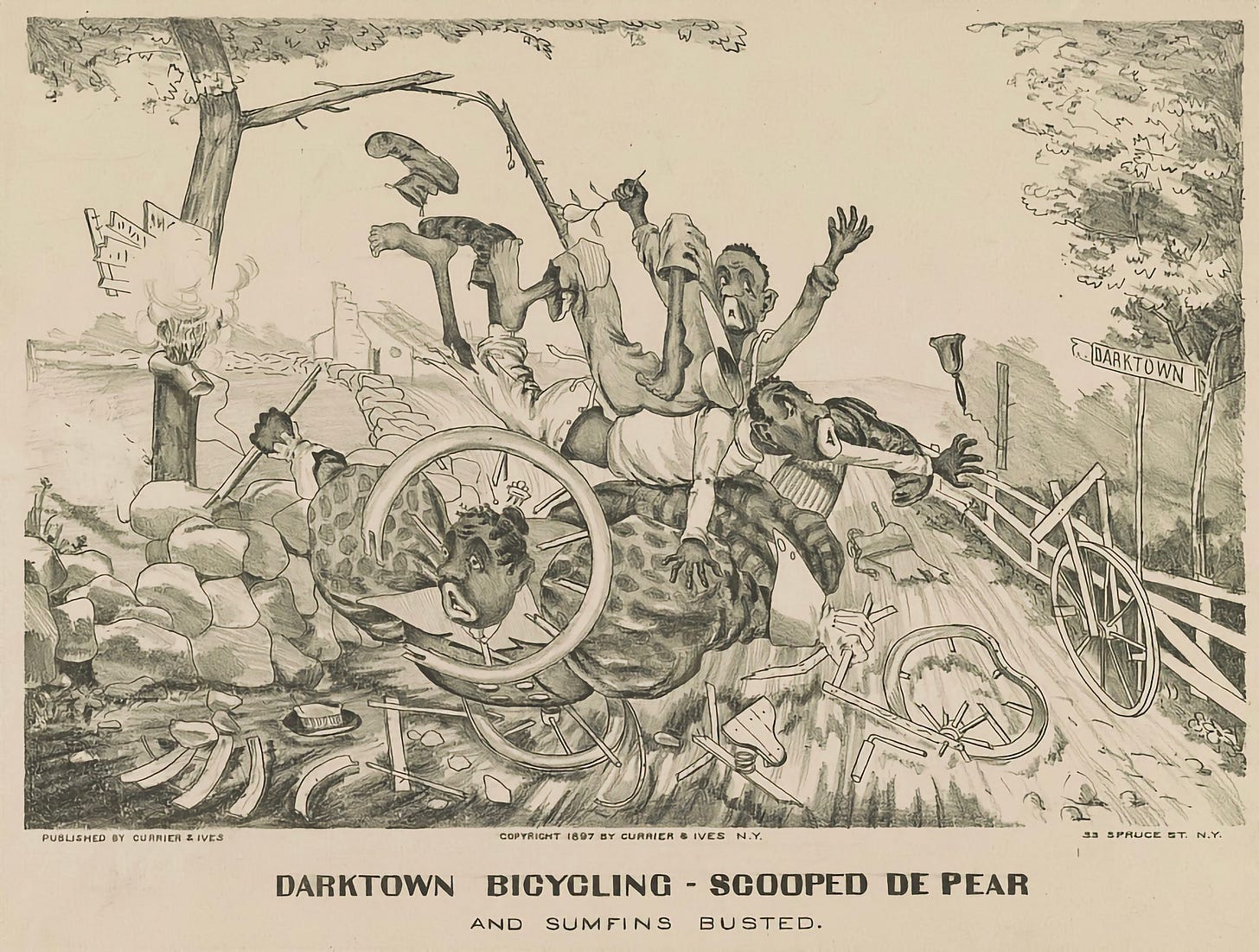

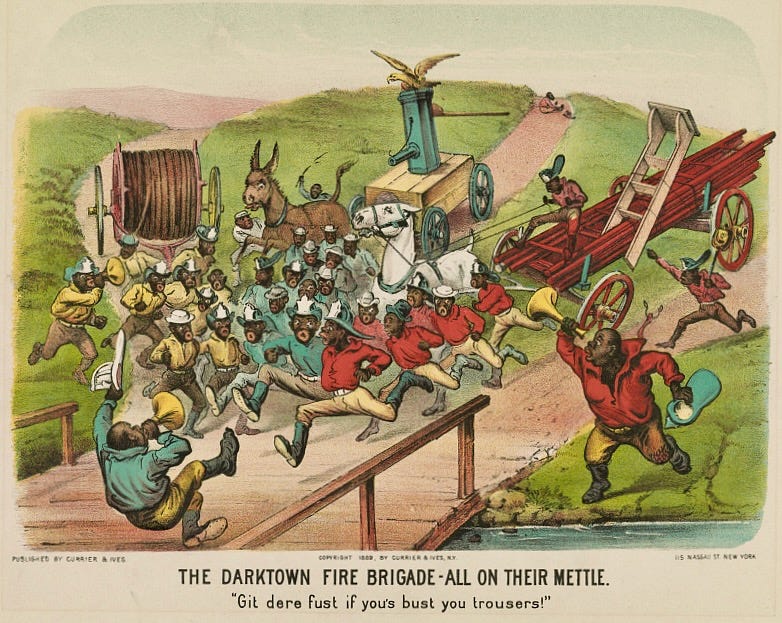

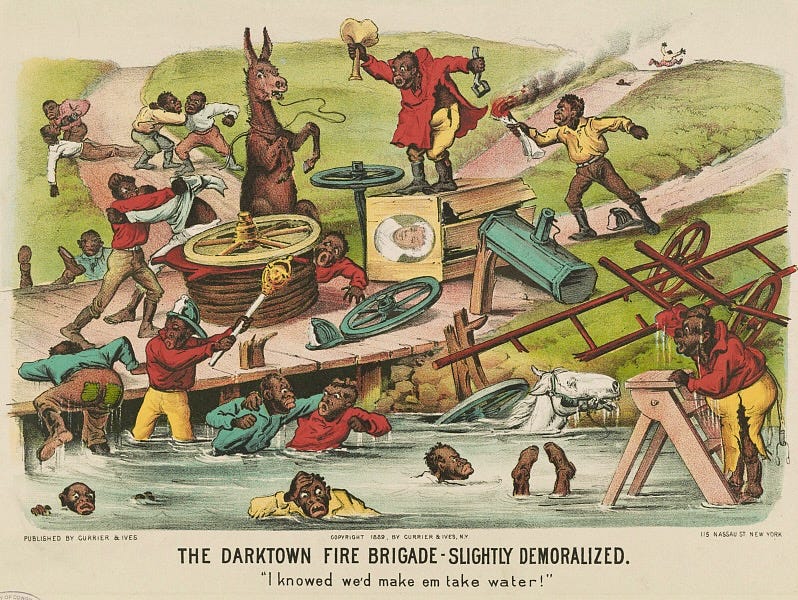

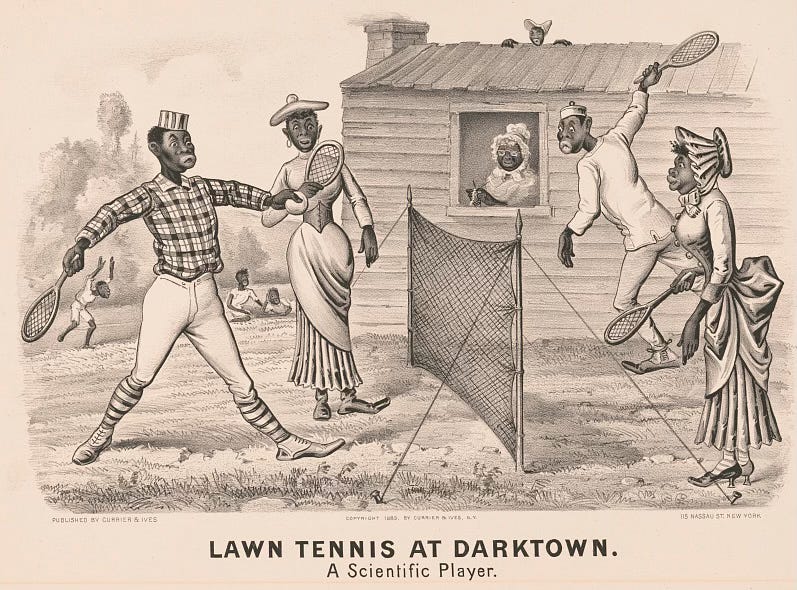

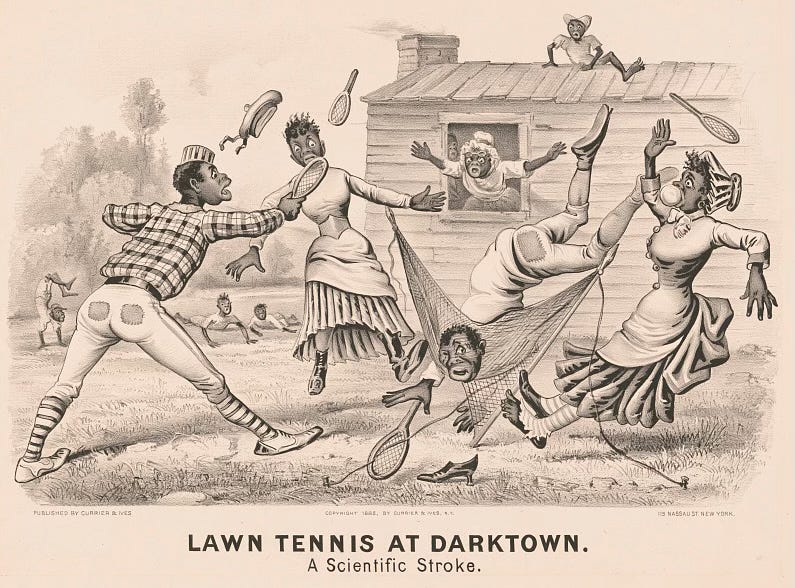

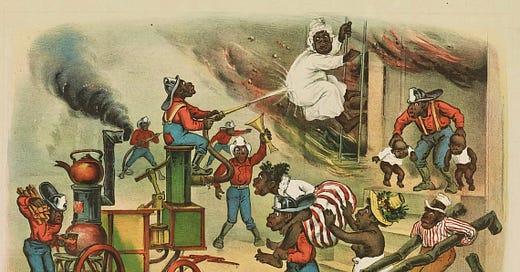

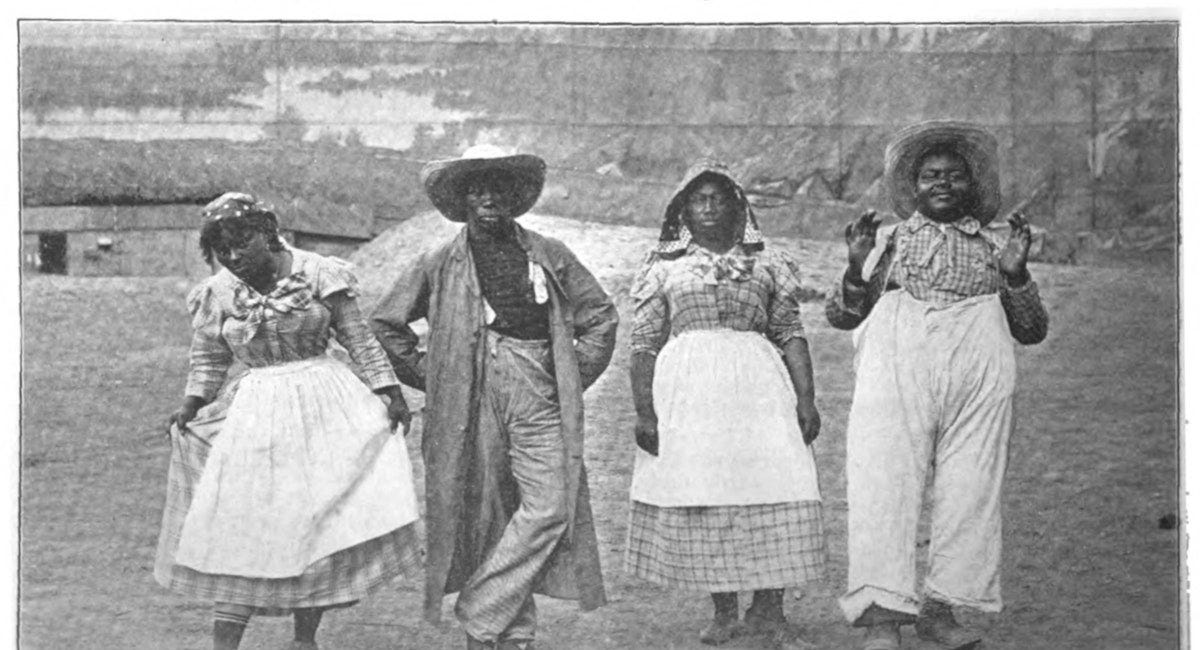

James’s story made me reflect on the Darktown Comics—a wildly popular series by Currier & Ives that turned Black Americans into cruel caricatures.

While Everett shows the strength and strategy behind the way language was used for survival, the Darktown Comics twisted similar imagery into tools of mockery and control.

The Darktown Comics: Weaponizing Representation

The Darktown Comics, churned out by Currier & Ives in the late 19th century, were bestsellers in their day—one image alone sold a staggering 73,000 copies.

These prints weren’t just entertainment. Born out of the Reconstruction era, they had a clear agenda: to keep white supremacy firmly in place.

This was the same era that gave us Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, where Jim’s humanity subtly challenged the dominant narratives of Black inferiority.

The Darktown Comics, however, wielded no such nuance. They aimed directly at the heart of Black ambition, using grotesque humor and exaggerated caricatures to mock and diminish any aspirations beyond the roles white society prescribed.

While Everett’s James highlights the calculated survival strategies of enslaved individuals, the Darktown Comics stripped these performances of context and dignity.

Instead, they turned Black aspirations and everyday life into a cruel joke, reshaping them into propaganda that mocked and belittled Black humanity.

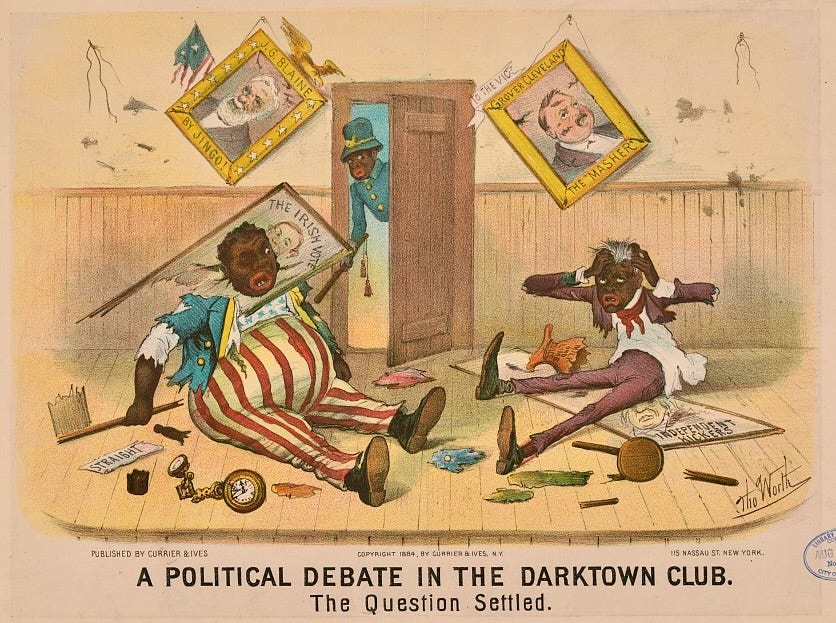

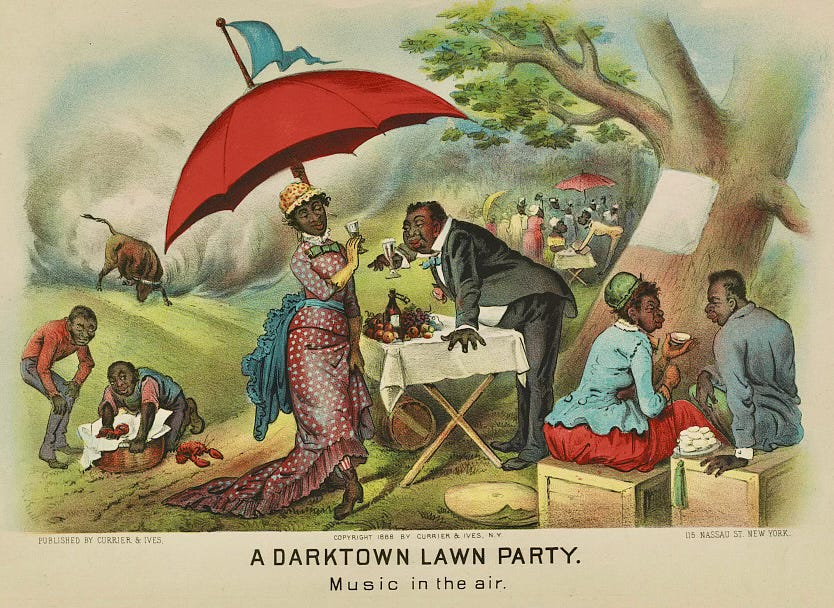

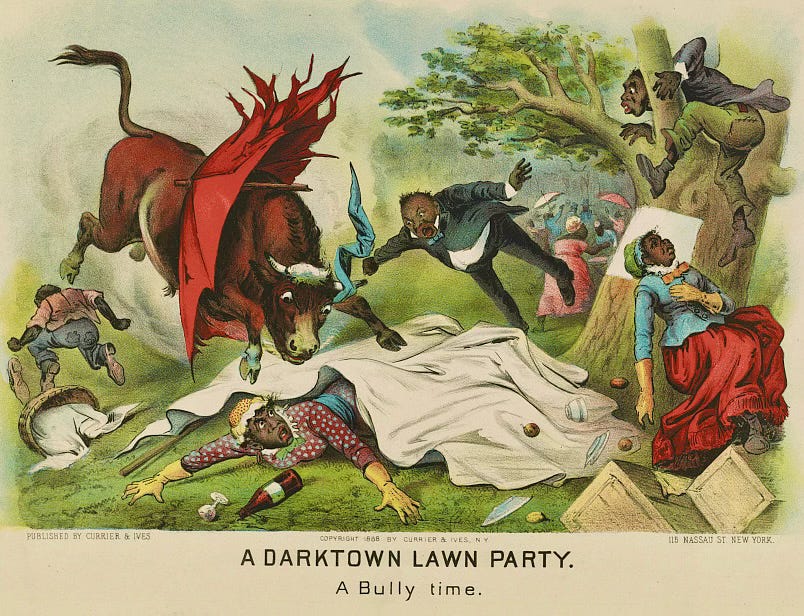

The Darktown series were often sold in pairs: one print showing Black Americans striving—dressing up, attending formal events, or engaging in civic life—and the next delivering the punchline, a grotesque caricature of failure.

Fine clothes became laughable costumes, ambition turned into incompetence, and dignity was reduced to absurdity.

These setups and punchlines didn’t just make a mockery of individuals; they worked to discredit the very idea of Black progress. By laughing along, viewers became complicit in reinforcing a vision of Black humanity as unnatural, ridiculous, and unworthy.

The message was clear: black equality was a farce, and any attempt to achieve it was doomed to fail.

Blacks “Attempting Whiteness”

The Darktown Comics loved to mock Black Americans who aimed higher—whether it was pursuing education, dressing sharply, or stepping into spaces dominated by white society.

These images didn’t just ridicule; they framed those aspirations as ridiculous and doomed from the start.

A common scenario featured Black men dressed in fine suits, attending formal events or engaging in activities associated with white society. Their exaggerated physical features and awkward postures made them objects of ridicule, while their aspirations were framed as delusional.

The message was clear: equality wasn’t just out of reach—it was a joke. And for white audiences uneasy about Black progress during Reconstruction, these depictions offered a kind of reassurance, reinforcing the idea that integration wasn’t just dangerous—it was impossible.

Blacks as Bumbling and Inferior

Another favorite theme in the Darktown Comics was portraying Black Americans as clumsy, lazy, or downright clueless.

These stereotypes weren’t just meant to get a laugh—they were crafted to send a message: Black people didn’t belong in positions of power or influence.

These weren’t harmless jokes—they were calculated attacks on the growing role of Black Americans in public life.

By tying Blackness to incompetence and failure, the comics worked to undermine any credibility Black people had in politics, business, or society.

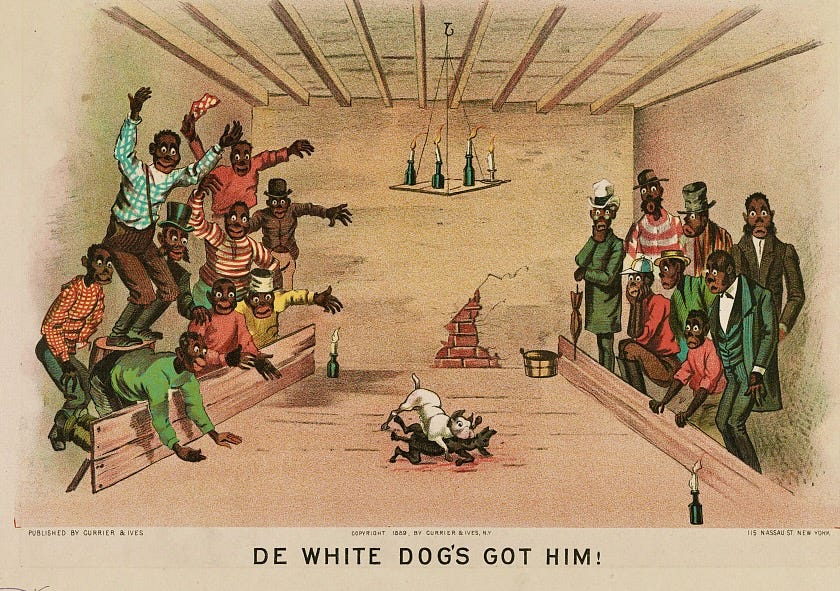

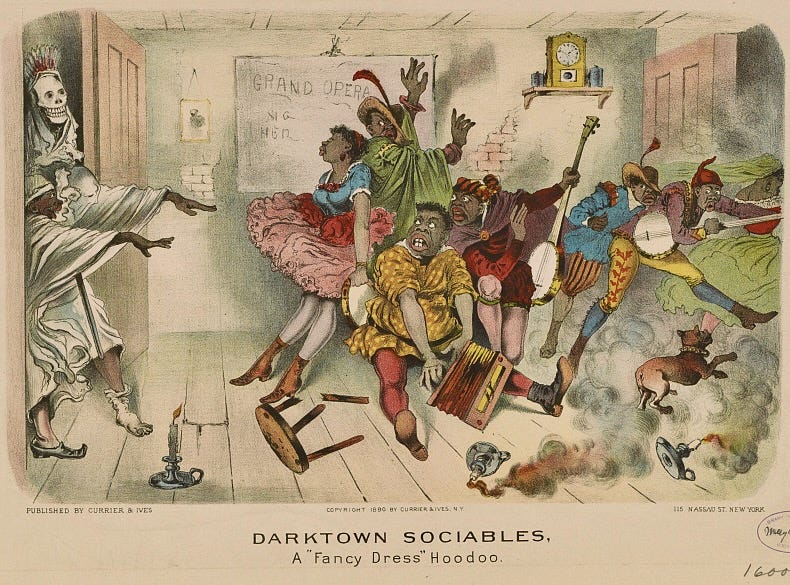

Subtle Intimations of White Supremacist Violence

Beneath their so-called humor, the Darktown Comics carried a darker message—an implicit threat of violence for any Black person who stepped out of their “place.”

These images didn’t just mock; they served as warnings, reminding audiences that ridicule wasn’t the worst fate awaiting those who challenged white supremacy.

This wasn’t just imagined. During Reconstruction, groups like the Ku Klux Klan used terror to crush Black political power, and these comics tapped into that climate of fear.

In Trial by Jury – The Verdict (1887), where a Black jury exonerates a Black defendant accused of stealing chickens. The defendant, thumbing his nose, mocks the jury, who hide strangled chickens behind their backs—one juror even blindfolded.

The image paints the courtroom as a farce and suggests that true “justice” lies not in legal proceedings but in extralegal acts like lynching. It’s a chilling scene, one that dehumanizes everyone involved while reinforcing the message that Black people don’t belong in civic life.

In De White Dog’s Got Him! (1889), Currier & Ives depict a dog fight as a grotesque allegory of racial violence. A white dog pins a black dog by the throat, while one group cheers in celebration and another watches in fear. Some even stare fearfully back at the viewer.

The blue-and-white checks and red stripes of the cheering faction’s shirts evoke the American flag, underscoring the association of white dominance with national identity.

Then there’s Darktown Sociables, “A Fancy Dress” Hoodoo (1890), Black performers flee in terror as two figures in white sheets, one wearing a skeleton mask, burst into the scene.

The taller figure, likely meant to represent Death, looms over the others, a clear echo of Klan terror. While a federal crackdown had disrupted the Klan’s national structure by the 1870s, localized acts and the lingering fear of their violence was alive and well—and Currier & Ives knew how to profit from it.

Reclaiming the Narrative

The contrast between Percival Everett’s James and the Darktown Comics says it all—one tells a story of resilience, the other twists Black identity into a punchline. Everett’s Jim is fully human: sharp, resourceful, and deeply aware of his world.

Currier & Ives‘ Darktown Comics couldn’t be further from that. They stripped Black Americans of humanity, using grotesque caricatures to mock their ambitions and prop up white supremacy.

Seen side by side, these stories show how far old stereotypes reach—and why reclaiming these narratives matters so much. James isn’t just a retelling; it’s a direct challenge to the ridicule and scorn used to dehumanize Black lives.

Looking back at these artifacts reveals how the past still shapes the present—and reminds us of the work still needed to unravel their legacy.

Here’s two more posts featuring racial humiliation from the same era …

Reenactment of Slavery in Brooklyn

A combination slavery cosplay, ethnographic exhibition, Black performance review, and all-around spectacle. …

The Human Zoo of 1904

The fair organizers arranged for more than 2,000 indigenous people from various regions and countries to be brought to the fairgrounds and exhibited in "living displays."

Thank you, Peter. Liker trump, the Civil War never ended. And neither will end, until WE, the people end it by realizing there is only ONE human animal extant today, Homo sapiens, There is only one Genus: Homo, and only one species: sapiens, there are no sub-species, no genetically distinct group. Like my favorite animal Felis cattus there are only cosmetic differences. While cats consider themselves to be superior to humans and dogs, they don't consider themselves superior to other cats.

If we had an ounce of intelligence, we'd recognize the same. As individuals we may be intellectually inferior to persons of true genius, and superior to those of lesser intelligence - but even that is questionable as it depends on education and distractability too. But skin, hair, eye color are purely cosmetic and have nothing to do with intellect, talent, beauty of features etc.

Powerful article, Peter. I’ll never think of Currier & Ives the same.