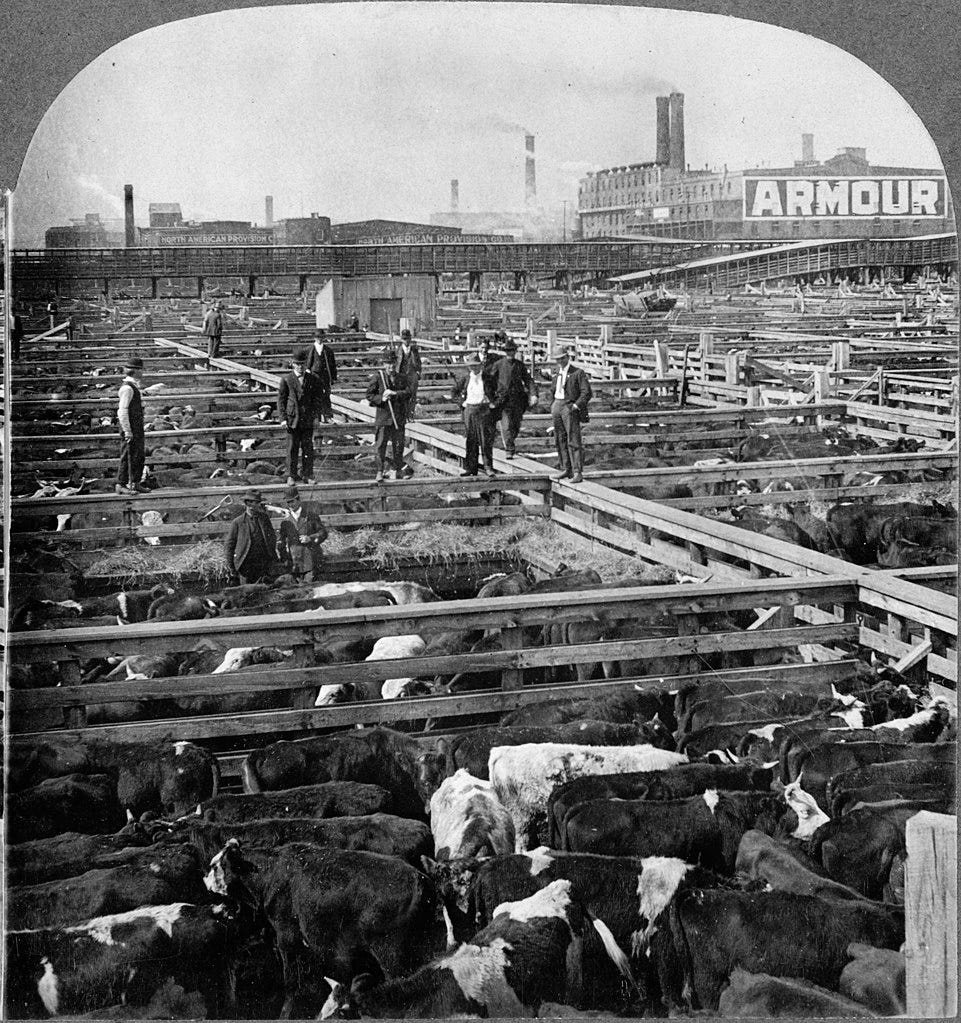

In the bustling streets of Chicago, the air was thick with the stench of blood and rotting flesh, a grim testament to the city's booming meatpacking industry. It was here, amidst the grime and gore of Packingtown, that the dark underbelly of America's industrial progress was laid bare.

The late 1800s and early 1900s had seen this industry thrive, powered by influential industrialists like Gustavus Swift and Philip Armour - whose innovations such as refrigerated railcars transformed meatpacking into a national enterprise.

Chicago became the heart of this transformation, attracting cattle and European immigrants - who provided the cheap labor necessary to process it. They toiled in grueling conditions, enduring long hours and hazardous environments for meager wages. The working conditions within these factories were nothing short of horrific.

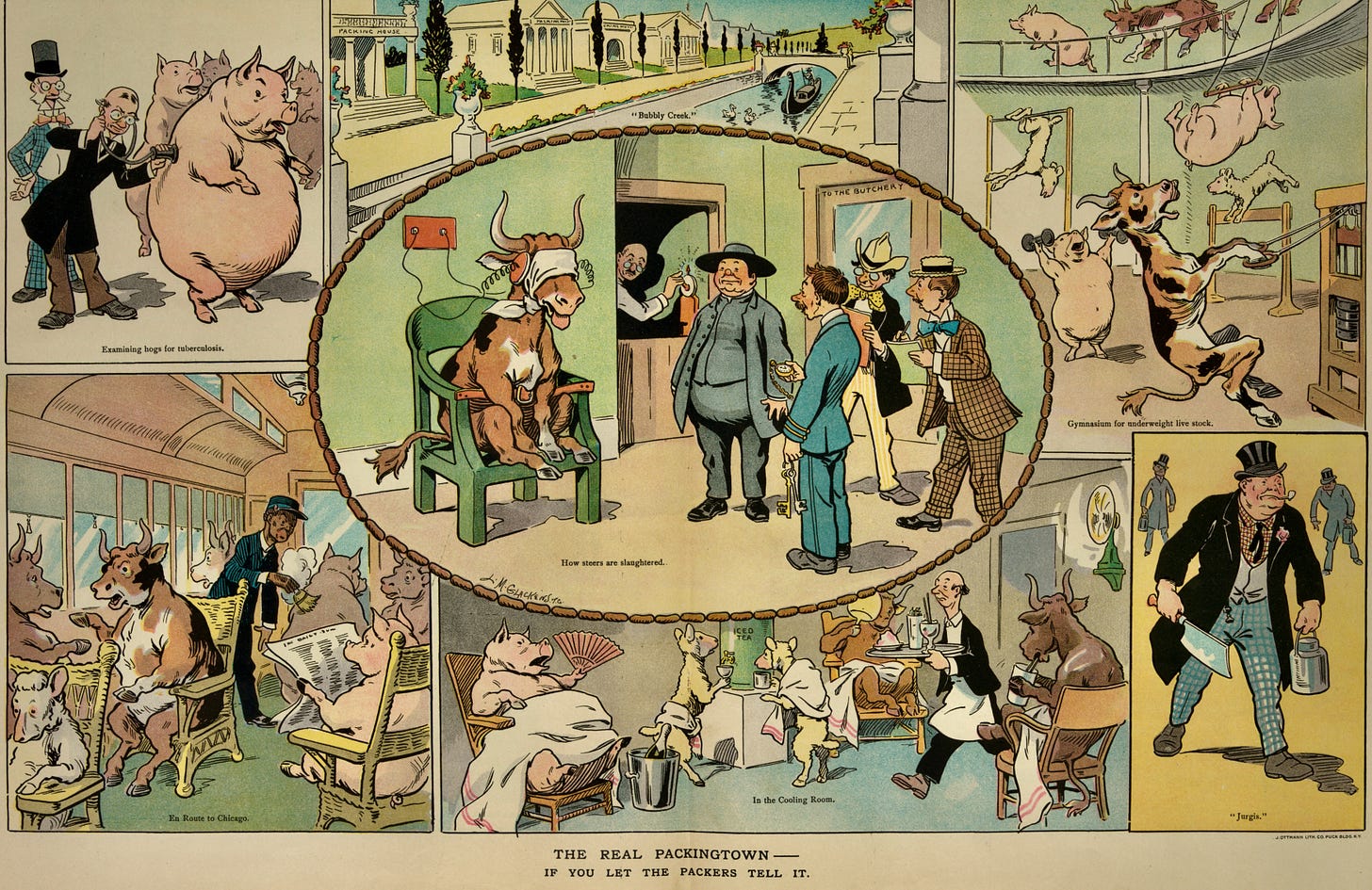

But in 1904, American muckraker, Upton Sinclair spent seven weeks gathering information while working incognito in the meatpacking plants of the Chicago stockyards for a socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason - which published his novel in serial form in 1905.

Five publishers rejected the work - deeming it too shocking for mainstream audiences, but in 1906 Doubleday published Sinclair’s novel in book format. In the first six weeks, the book sold 25,000 copies. It has been in print ever since.

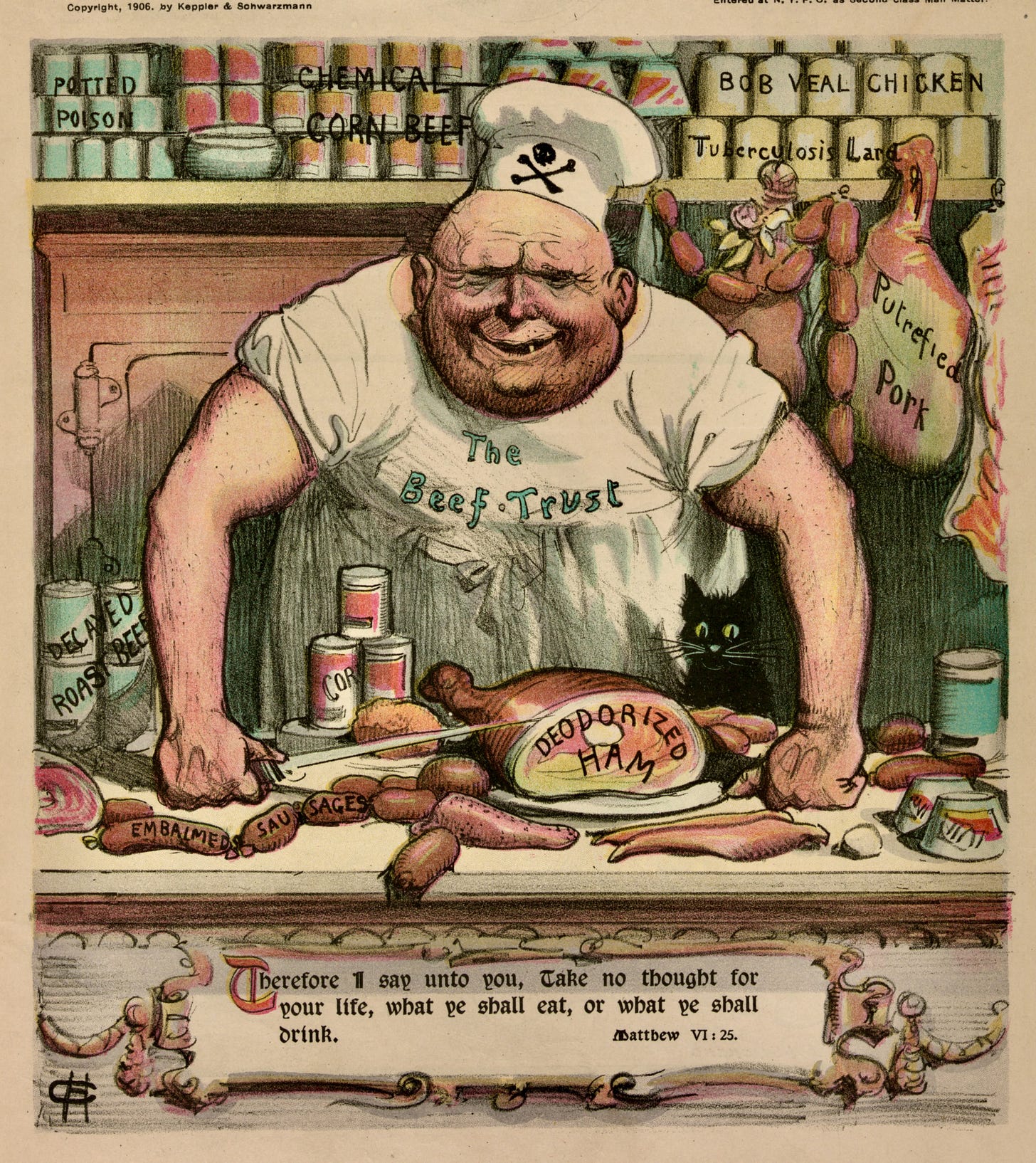

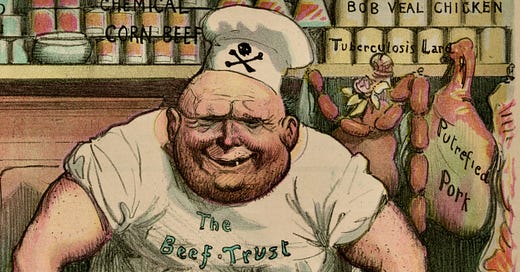

Sinclair’s “The Jungle” horrified Americans with its vivid depictions of the meatpacking house:

“… old sausage that had been rejected, and that was moldy and white—it would be doused with borax and glycerine, and dumped into the hoppers, and made over again for home consumption. There would be meat that had tumbled out on the floor, in the dirt and sawdust, where the workers had tramped and spit uncounted billions of consumption germs.

Workers faced daily physical dangers. One worker said,

“And as for the other men, who worked in tank rooms full of steam, their peculiar trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting,—sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard!.”

The brutality extended to the youngest laborers. Children as young as eight were employed in these grim conditions, performing perilous tasks. A young boy explained:

“I worked from dawn till dusk. My job was to scoop up the entrails and throw them into a bin. My hands were always raw, and the smell clung to my skin no matter how much I washed.”

The public health implications of such unsanitary practices were devastating. Contaminated meat frequently reached consumers, leading to widespread disease.

Sinclair’s account is chilling:

“The meat would be shoveled into carts, and the carts would be taken to the chutes, and from there it would go into the hoppers with fresh meat, and sent out to the public’s breakfast. The workers in the department would be spitting tuberculosis on the floor, and the meat would be shoveled from the filthy floor, and would go into the hoppers with dirt and dust and floor filth.”

This cavalier handling of foodstuffs led to outbreaks of diseases like tuberculosis and botulism, prompting newspapers to run fear-mongering stories and sparking public outcry.

Beyond the immediate human toll, the meatpacking industry also wrought environmental havoc. Waste products were dumped indiscriminately, polluting rivers and the air. The Chicago River became a flowing cesspool, leading to high rates of respiratory and waterborne diseases in local communities. One resident recounted,

“The river ran red with blood. The smell was unbearable, and it wasn’t uncommon to see dead animals floating by. Our children were constantly sick.”

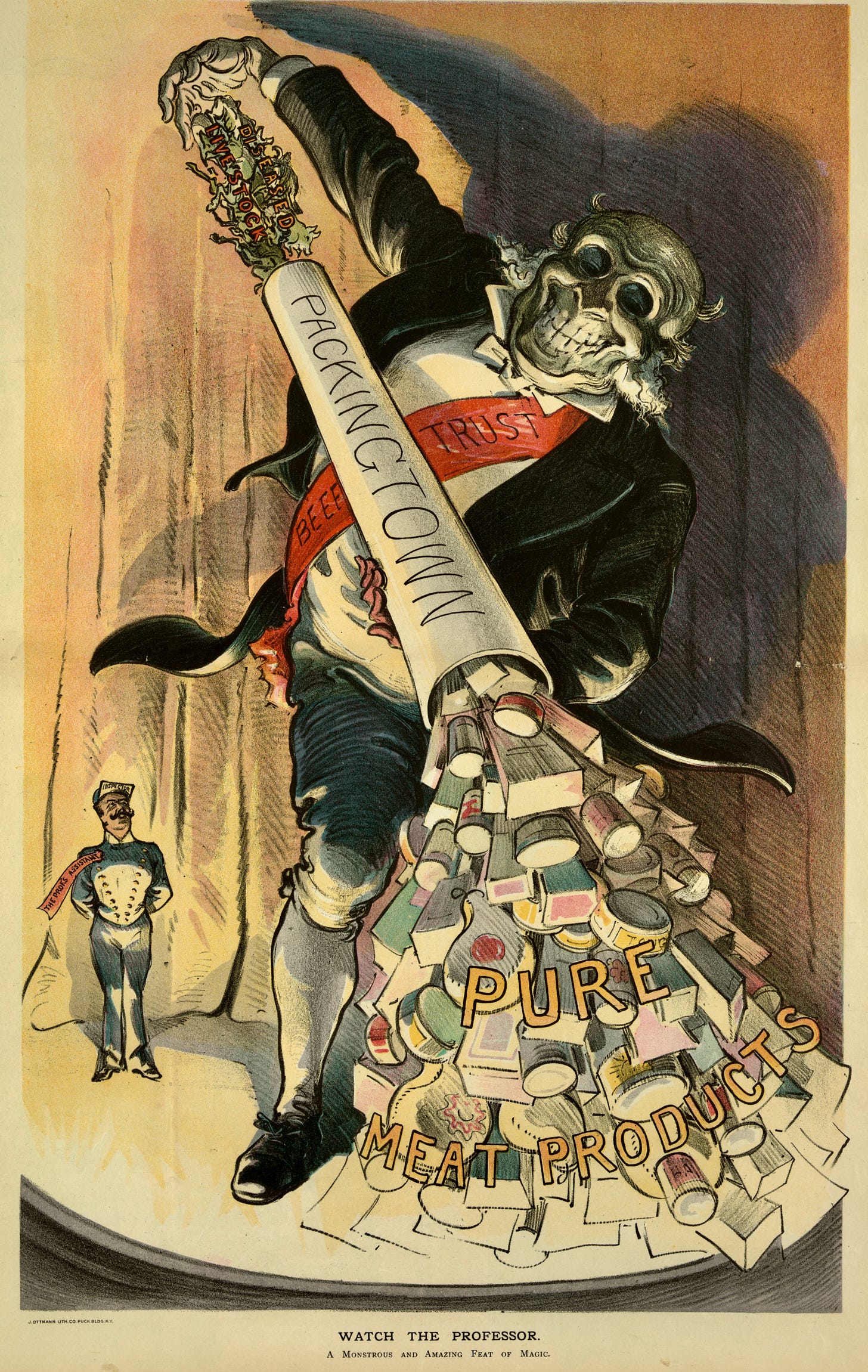

Reform did not come easily or quickly. And the meatpacking industry fought back with extensive public relations campaigns to counteract the negative publicity. They published advertisements and press releases to reassure the public about the safety and quality of their products.

It took the tireless efforts of muckraking journalists and activists to expose the industry's abuses and advocate for change. Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” played a leading role in raising public awareness, its vivid and disturbing portrayals shocked readers and galvanized support for legislative action.

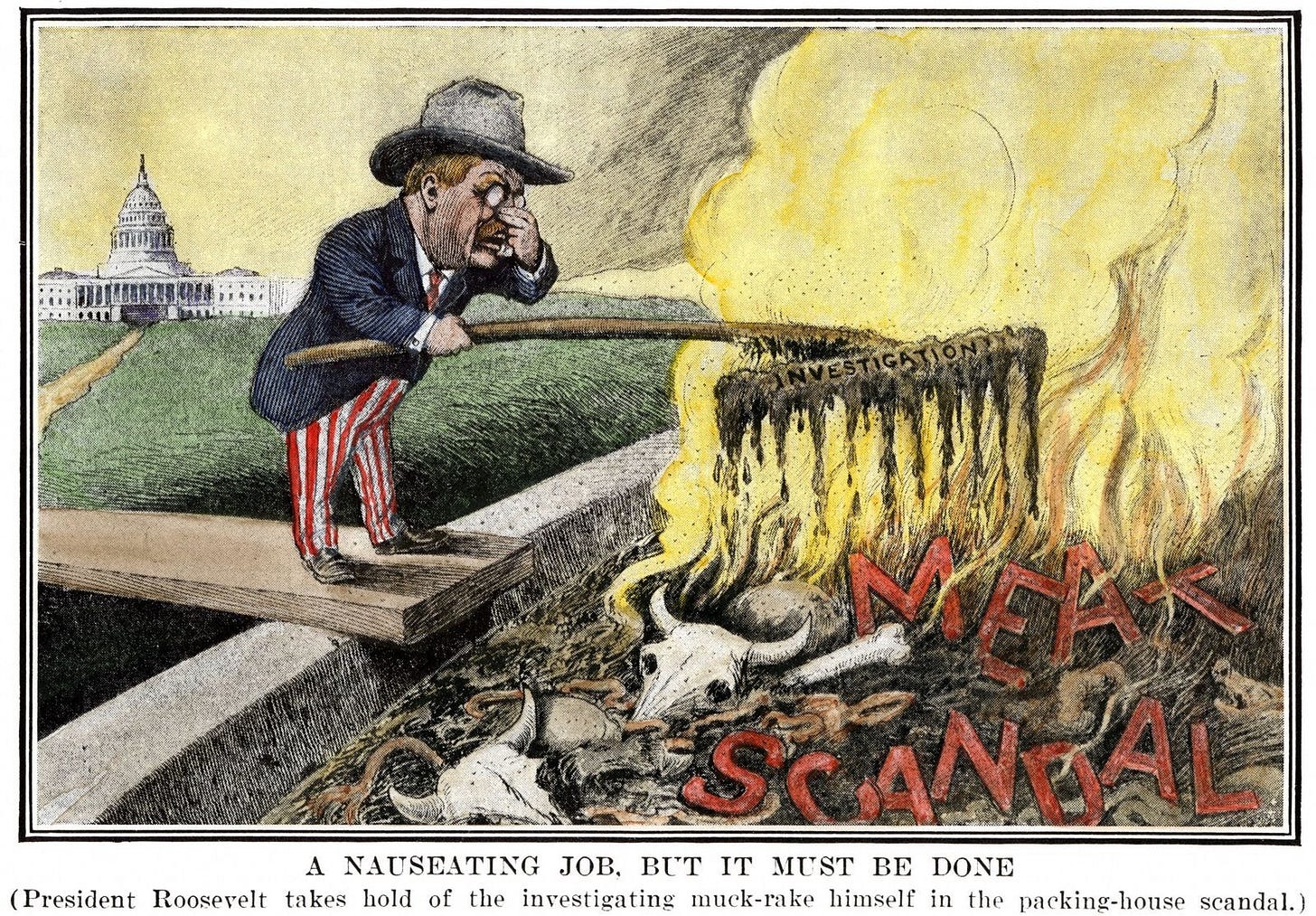

Initially, President Teddy Roosevelt was skeptical of the claims made in Sinclair’s novel, viewing them as exaggerated and possibly politically motivated given Sinclair’s socialist leanings. However, he recognized the growing public concern and the potential political ramifications of ignoring such a scandal.

After he appointed a commission to study the meat packing industry, Roosevelt skillfully used the findings of the “Neill-Reynolds Report” to apply pressure on Congress.

In response to Roosevelt’s pressure and the mounting public outcry, Congress passed the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act on June 30, 1906. These acts set sanitary standards for meat processing and prohibited the sale of adulterated or misbranded meat products. They also mandated regular inspections of meatpacking facilities by federal inspectors.

Despite these early 20th-century reforms, modern-day worker safety and health abuses continue to plague the meatpacking industry. Workers today still face hazardous conditions, low wages, and high rates of injury.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues, revealing how crowded and unsafe working environments in meatpacking plants could lead to massive outbreaks among workers. Investigative reports have highlighted ongoing issues such as insufficient protective equipment, poor ventilation, and pressure to work despite illness or injury, drawing eerie parallels to the conditions depicted in “The Jungle” over a century ago.

More Chicago?

Women on the Warpath (1900)

This is the header image to a full page Sunday story on women and how Chicago police records document women’s weapon of choice. The article is decidedly anti-female and casts women as taking advantage of unarmed men. WOMAN HAS PET WEAPONS. Grabs First Thing Comes to Hand Hit Man.

Chicago's Gangland Map and Dictionary (1931)

Bruce-Roberts’ map of Chicago’s “gangland,” produced in 1931 and “designed to inculcate the most important principles of piety and virtue in young persons and graphically portray the evils and sin of large cities,” is a sensational and humorous approach to documenting crime in the city. Bruce-Roberts is not a person, but a company.…

I remember being inspired by (If that's the right word) The Jungle, probably around my 9th or 10th grade year in high school. I was really fortunate to be exposed to these ideas in the deep south where I grew up, and where this sort of history isn't necessarily being taught as much today.

OMG! A vegetarian's nightmare!