Respectable Hate

When White Citizens’ Councils were the "Klan in a Suit"

In the 1950s, as the civil rights movement gained momentum, the White Citizens’ Councils emerged across the South, presenting themselves as the "respectable" face of segregation.

Unlike the Ku Klux Klan, these councils didn’t rely on hoods and violence; instead, they wielded economic power and social influence to maintain white supremacy under a veneer of respectability.

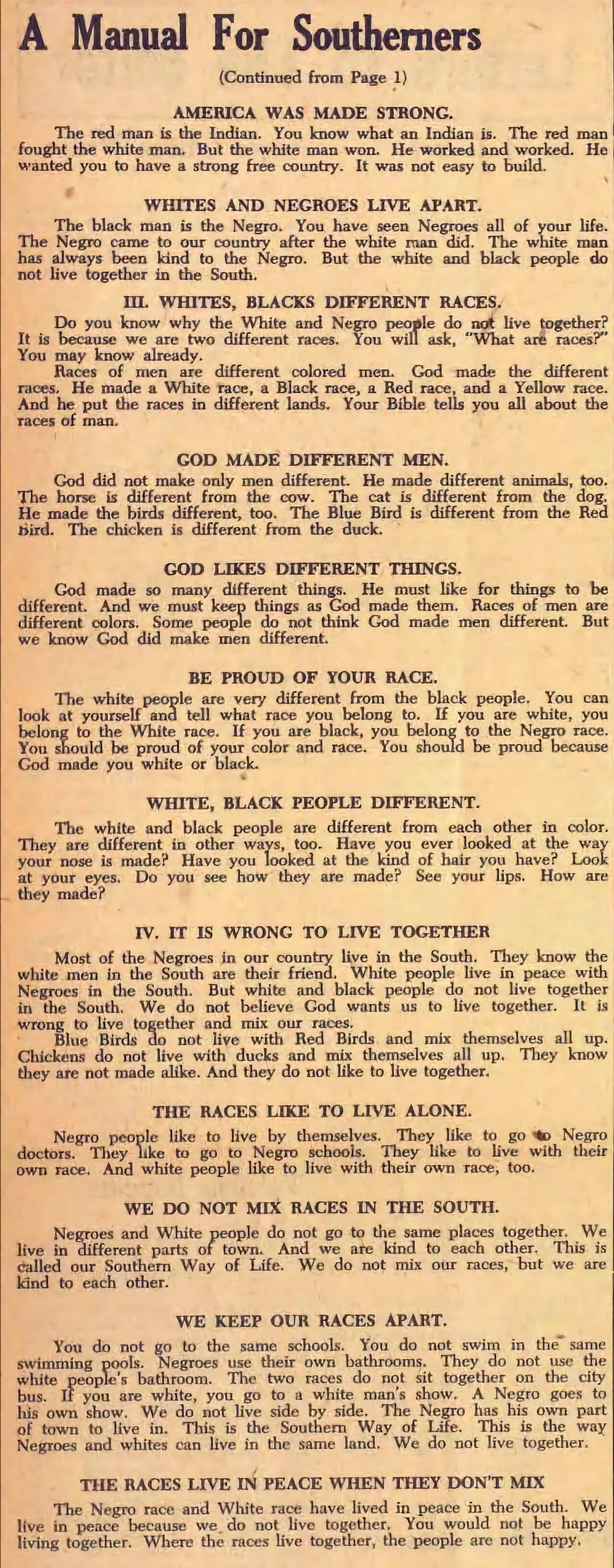

To reinforce their message, the Councils distributed propaganda like “A Manual For Southerners,” published in 1957.

GOD MADE FOUR RACES

GOD PUT EACH RACE BY ITSELF

WHITE MEN BUILT AMERICA

This manual was aimed at young children, teaching them that segregation was not just a social preference but a divine mandate.

It justified segregation as both natural and necessary.

The White Citizens’ Councils were born in response to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which upended the racial hierarchy of the South. These councils, composed of local businessmen, politicians, and community leaders, used their influence to enforce segregation.

The White Citizens’ Councils were the “white-collar Klan.”

They boycotted businesses that supported integration, fired teachers who advocated for civil rights, and manipulated mortgage and loan policies to punish dissenters. By controlling the economic levers of power, they maintained racial inequality while claiming to defend "Southern traditions."

Under pressure from the White Citizens Councils, in 1956 the Louisiana State Legislature passed a law mandating racial segregation in nearly every aspect of public life. It read, in part:

An Act to prohibit all interracial dancing, social functions, entertainments, athletic training, games, sports, or contests and other such activities; to provide for separate seating and other facilities for white and negroes. [lower case in original]

… white persons are prohibited from sitting in or using any part of seating arrangements and sanitary or other facilities set apart for members of the negro race. That negro persons are prohibited from sitting in or using any part of seating arrangements and sanitary or other facilities set apart for white persons. ~ Source

At the heart of the Councils’ strategy was economic intimidation. Business owners who supported integration found themselves targeted by boycotts, while white workers who spoke out were blacklisted.

Black firings and evictions of were part of a systematic plan to thwart civil rights activism and prevent Black people from voting.

On August 31, 1962, Fannie Lou Hamer and other Black residents of the Mississippi Delta traveled to Indianola to register to vote. Soon after, she and her husband were evicted from the Marlowe plantation where they had been sharecroppers for 18 years.

Homeless and denied work, the Hamers moved into temporary housing in nearby Ruleville, where white shooters targeted their home less than two weeks later.

Undeterred, Mrs. Hamer returned to register to vote that December, and told the circuit clerk: “You can’t have me fired anymore ‘cause I’m already fired, [and] I won’t have to move now, because I’m not living in a white man’s house.”

In 1963, Mrs. Hamer was brutally beaten by police for her continued activism, but went on to heroically lead a movement demanding political representation for Black people in the South. ~ Source

The Councils’ actions were a calculated attempt to suppress the civil rights movement without resorting to overt violence, presenting their cause as a legitimate defense of a threatened way of life.

Though the Councils sought to maintain a veneer of respectability, the racist hatred they fueled often spiraled beyond their control.

Medgar Evers, a Black WWII vet and NAACP organizer in Mississippi was assassinated in 1963 by Byron De La Beckwith - a member of the Citizens' Council and the Klan.

Emerging from his car and carrying NAACP T-shirts that read "Jim Crow Must Go", Evers was shot in the back. Initially refused entry to a nearby hospital because of his race, he died an hour later.

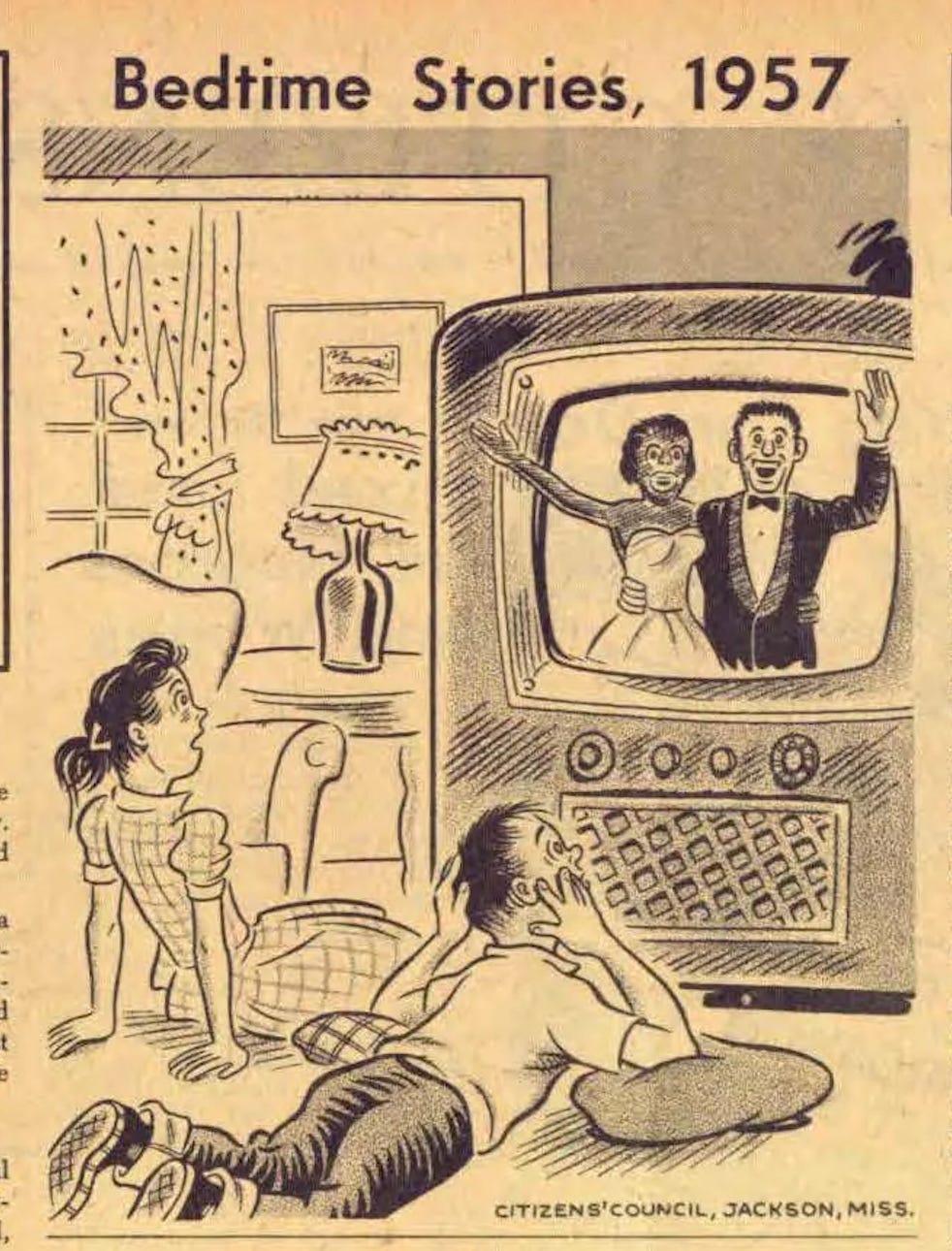

The White Citizens’ Councils engaged in a campaign of fear-mongering. They warned that integration would lead to societal collapse, using apocalyptic language to stoke fears of racial mixing and moral decay.

This rhetoric, rooted in anxiety about social change, resonates with today’s opposition to Critical Race Theory (CRT). Just as the Councils framed integration as a threat to civilization, modern anti-CRT activists portray racial education as an existential danger to American values.

The tactics of the White Citizens’ Councils have a clear echo in today’s political landscape. The use of economic pressure, the manipulation of public narratives, and the appeal to "protecting our way of life" are all strategies employed by modern movements that oppose racial justice.

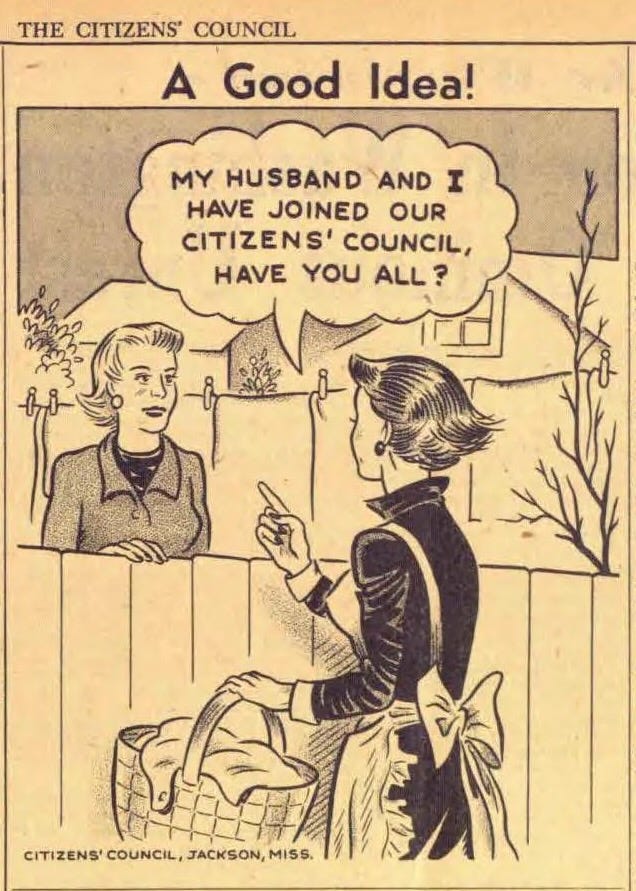

Newspaper clippings are from: The Citizens' Council, Vol 2 No 5 February 1957

See full issue with even more racism: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4

More on America’s legacy of racism

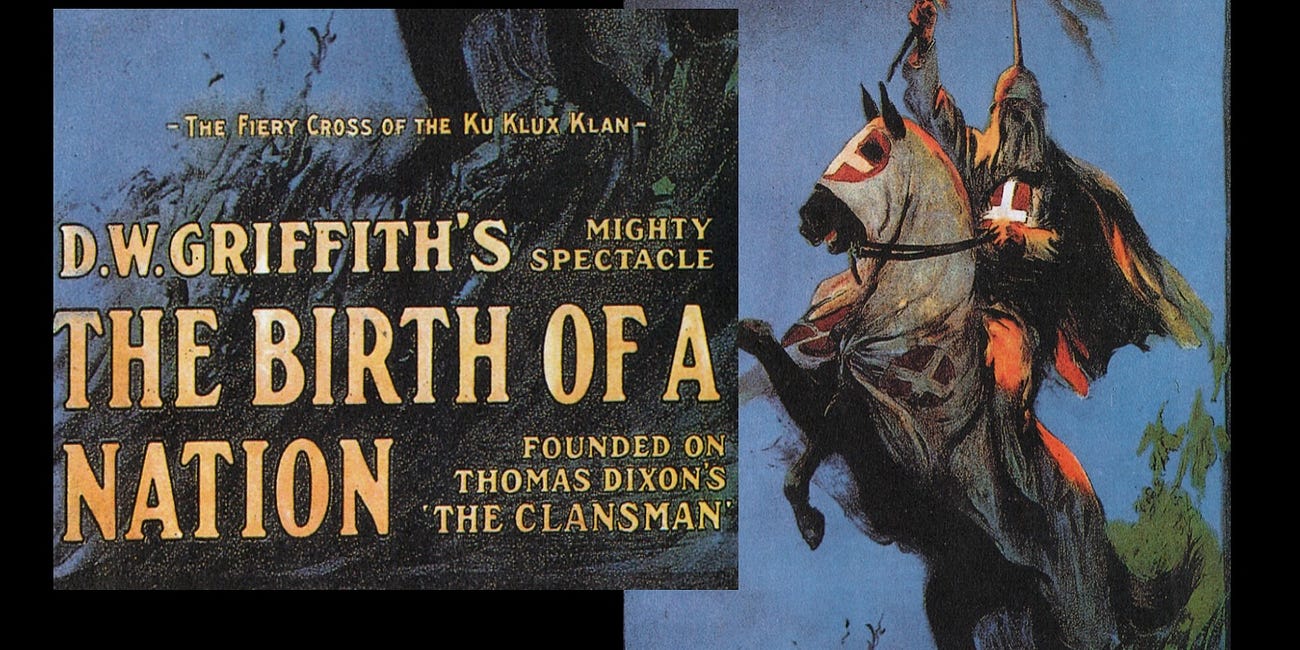

Marketing a Myth

In 1915, D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation was a cinematic milestone, revolutionizing the art of filmmaking with its innovative techniques. Yet, beneath its technical prowess lay a deeply troubling narrative that glorified the Ku Klux Klan and propagated the myth of the "Lost Cause."

The Human Zoo of 1904

How the St. Louis World’s Fair Celebrated America by Dehumanizing Others - among the dazzling attractions, there was also a dark and disturbing spectacle: the human zoo

History tends to rhyme, doesn't it?

Some things haven’t changed much.