In 1942, the U.S. government resurrected the centuries-old Alien Enemies Act of 1798- and dragged Japanese Americans from their homes, fenced them behind barbed wire, and called it “necessary.”

On March 15, President Trump resurrected the same law--dusted off from our darkest hours--to jail alleged Venezuelan gang members in a maximum-security prison in El Salvador without trial, painting entire communities as enemies once more.

Eight decades after we pledged “never again,” the same fear-based rhetoric has come roaring back. Once again, an entire group is labeled “enemy,” stripped of due process, and swept aside by a law that should never have been revived.

Fueled by fear then, propelled by fear now. The same script runs on repeat—demonize, detain, deny due process.

Early Japanese American Communities

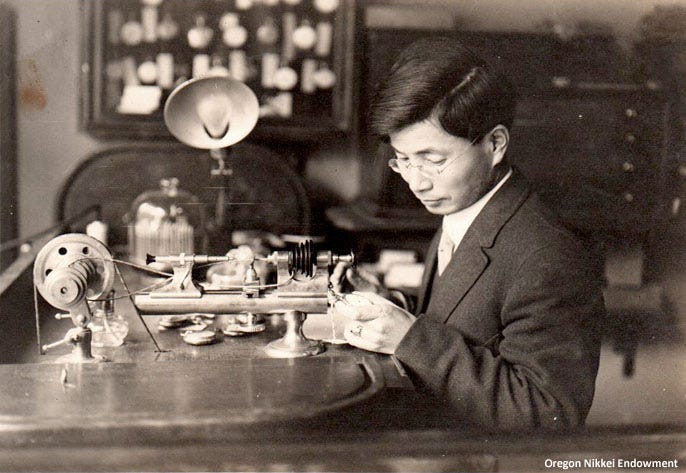

Japanese workers first arrived on the U.S. mainland in the late 19th century, taking difficult jobs in railroads, sawmills, canneries, and agriculture—part of the wider tide of migrants seeking new opportunities. However, their growing presence quickly sparked nativist opposition in California and other Western states, where anti-Asian sentiment led to organized campaigns, restrictive state legislation, and federal policies aimed at curtailing further Japanese immigration.

Growing nativism in California and other Western states soon targeted the newcomers, culminating in the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907–08, which essentially halted further labor migration from Japan.

A loophole allowed family members to join those already in the U.S., prompting the arrival of thousands of “picture brides” and the growth of Japanese American families on the West Coast. Despite laws barring them from citizenship and land ownership, these immigrants persisted.

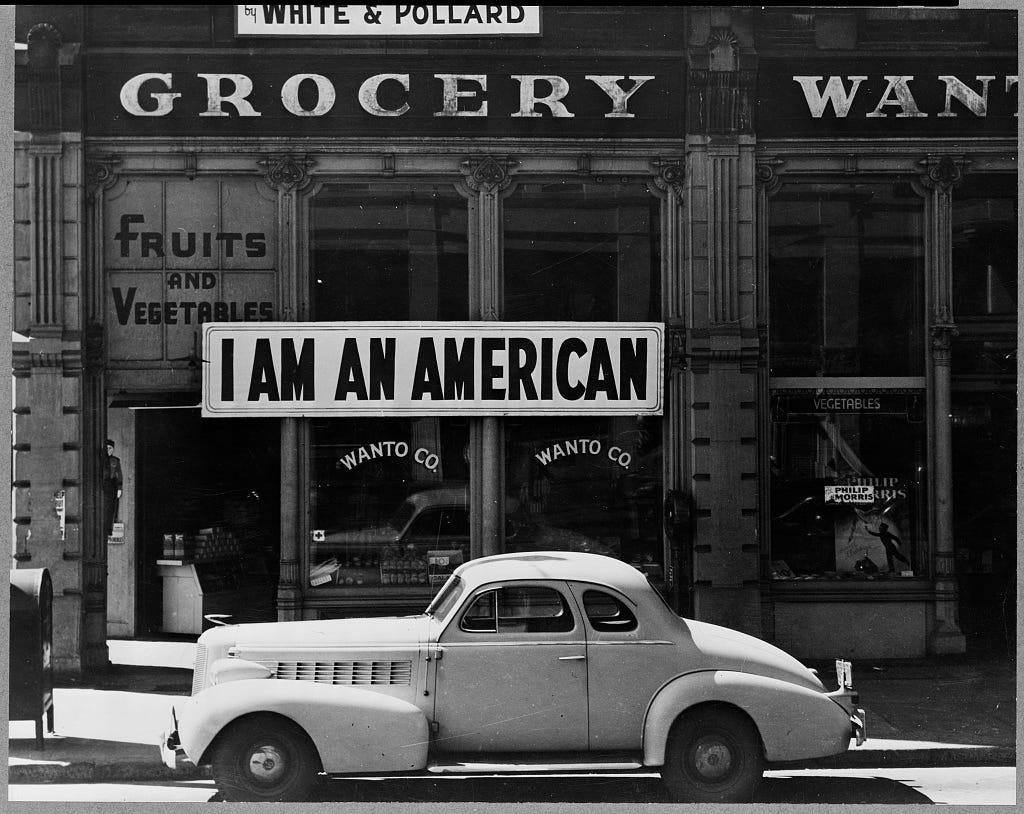

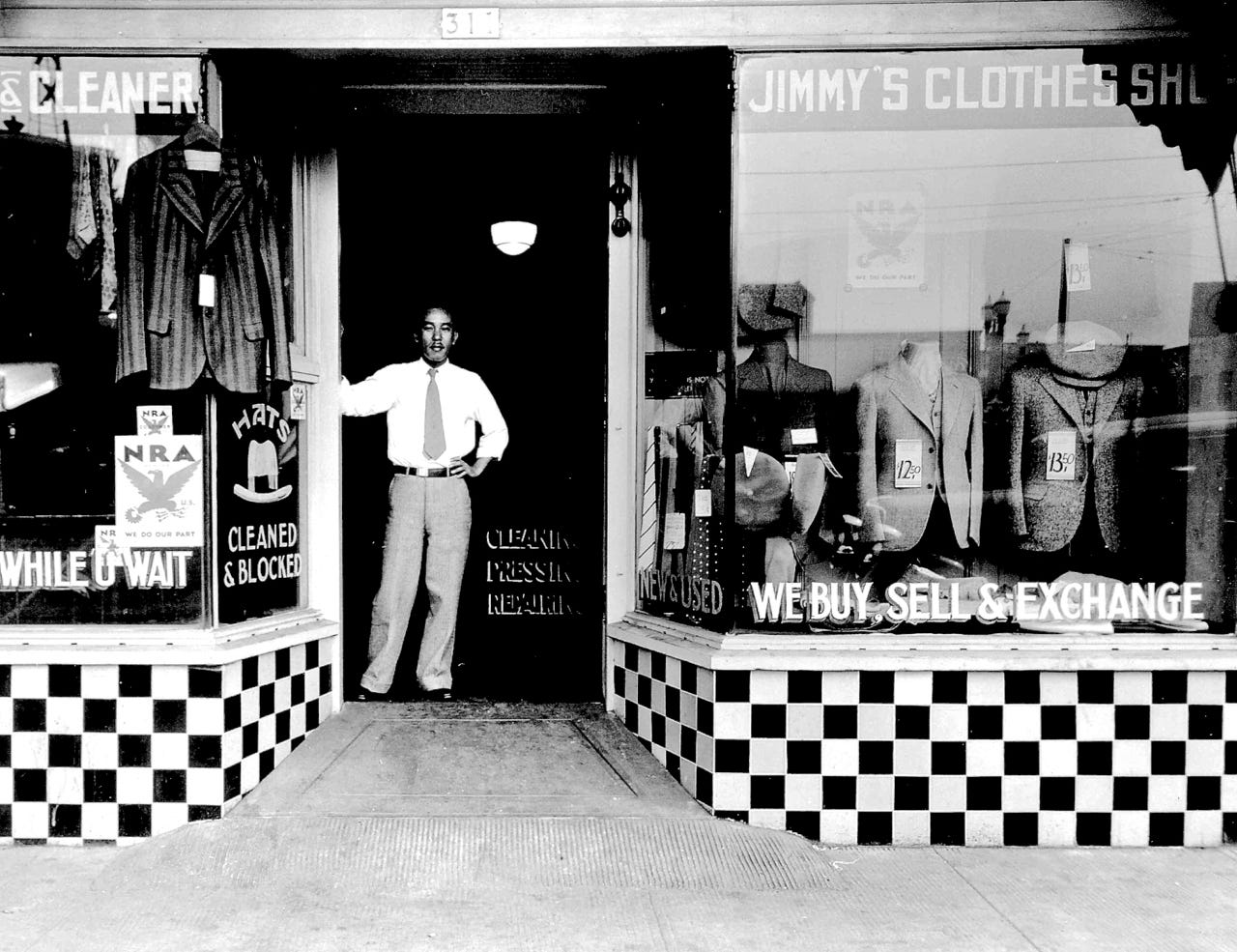

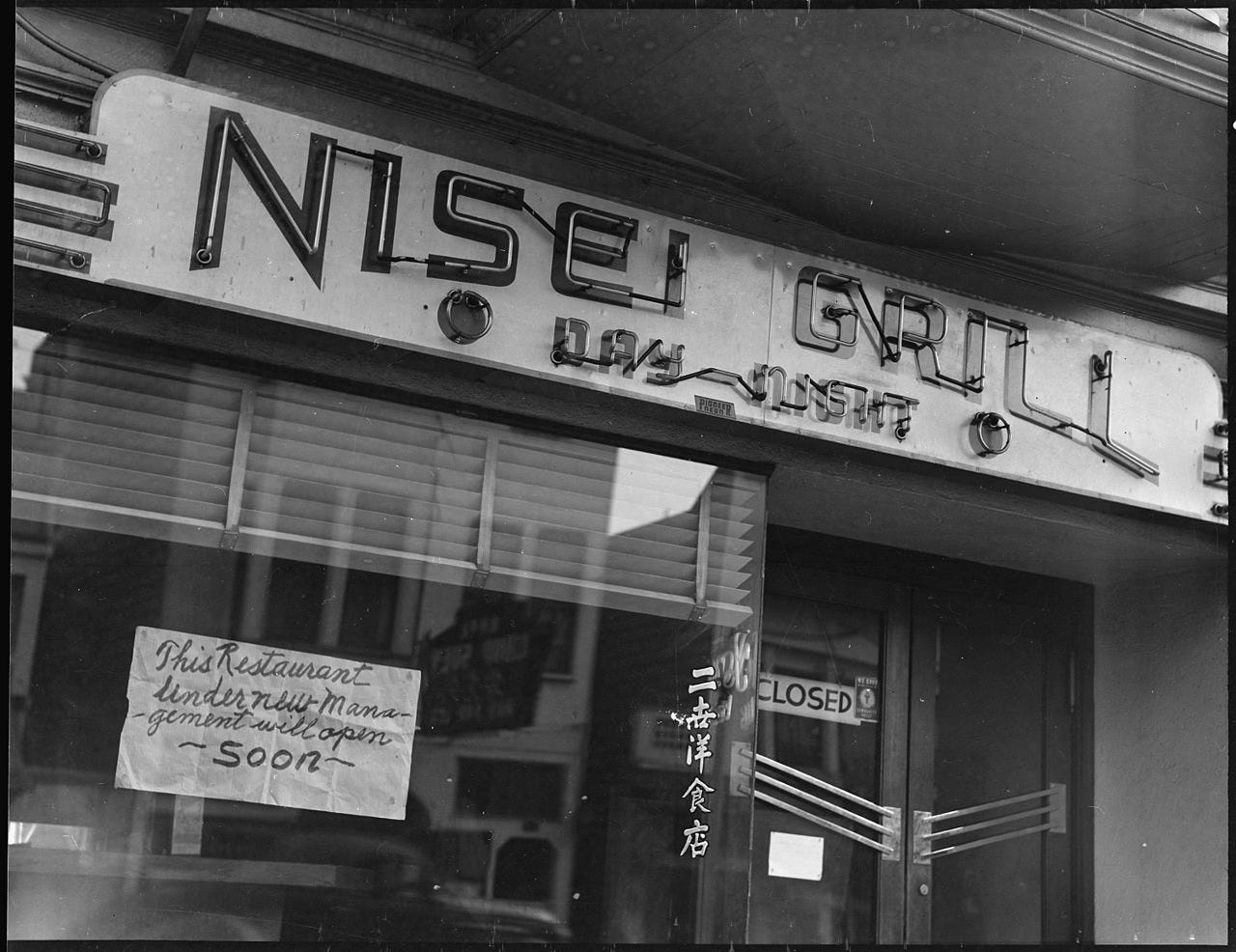

By the 1920s and 1930s, Japanese Americans had built vibrant enclaves along the West Coast--thriving Japantowns. Families established grocery stores, restaurants, laundries, and churches, all woven into the city’s broader commercial and social life.

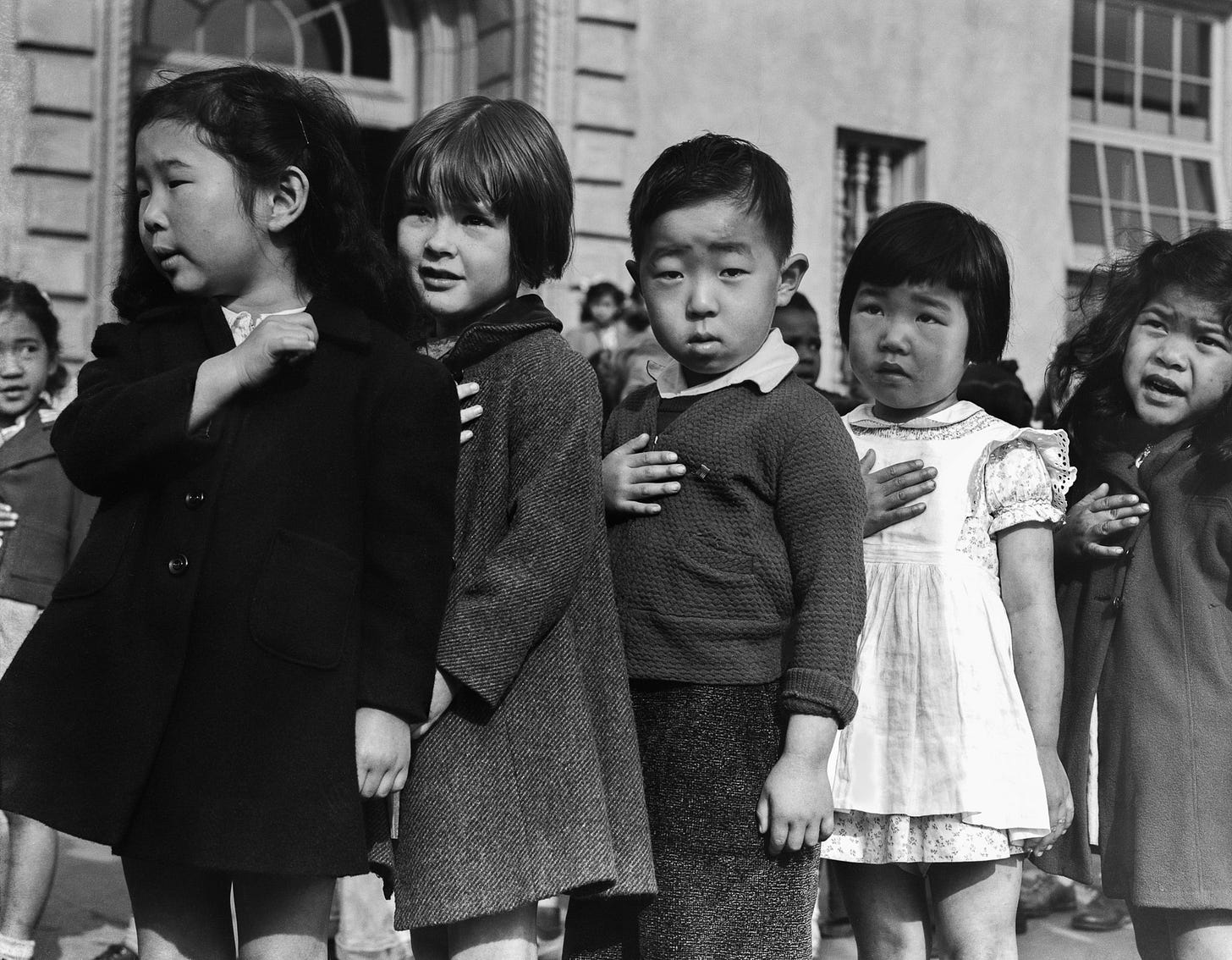

Far from being newcomers, many were second- or even third-generation citizens (Nisei and Sansei)—fully American, yet constantly under the cloud of being seen as “perpetual foreigners.”

The Shock of Pearl Harbor

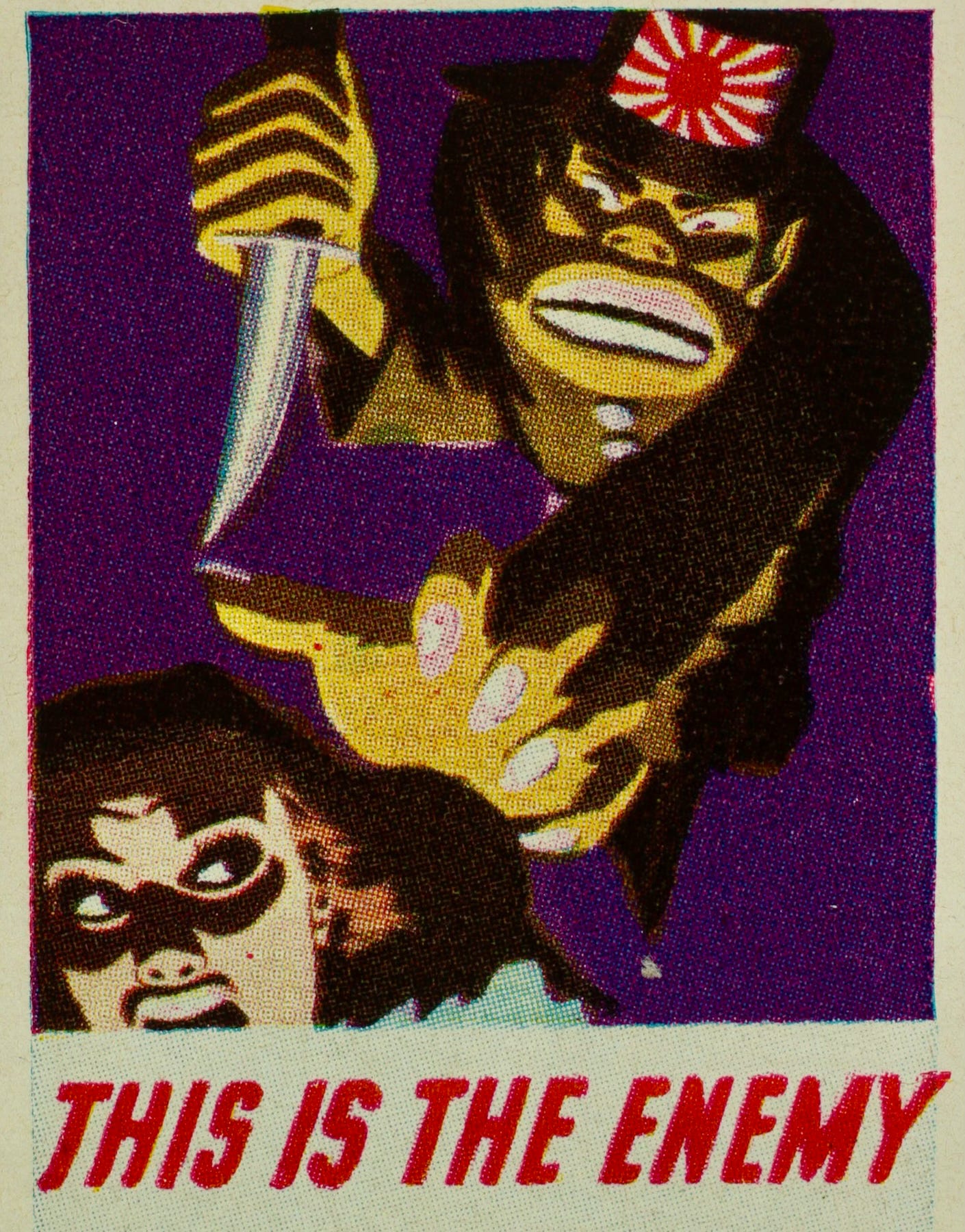

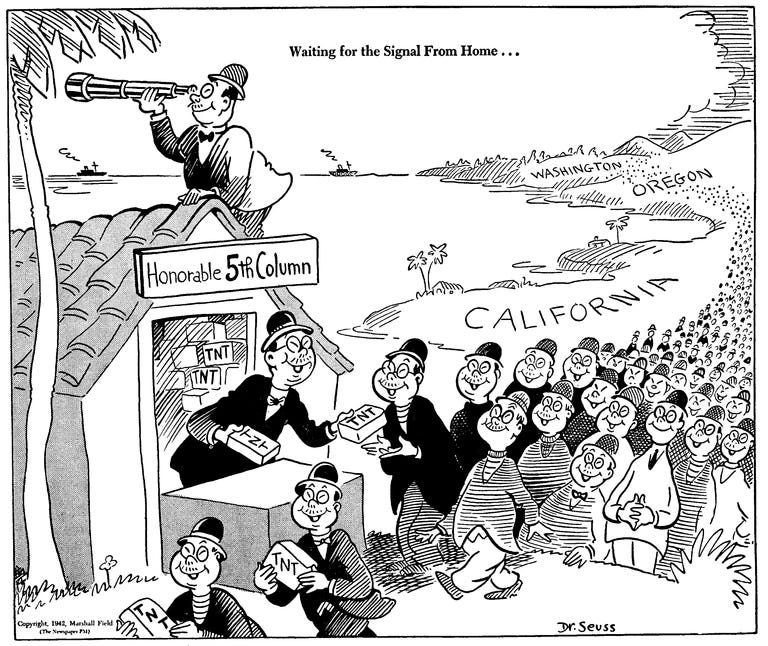

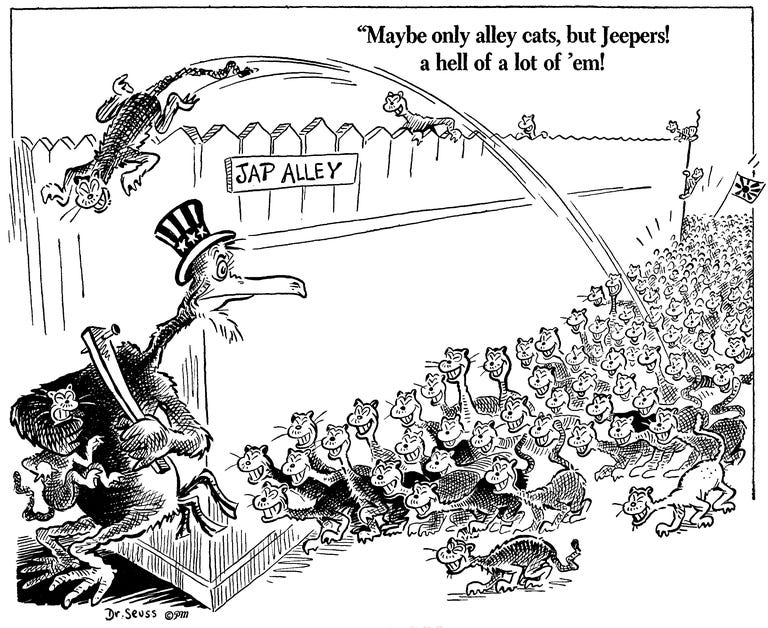

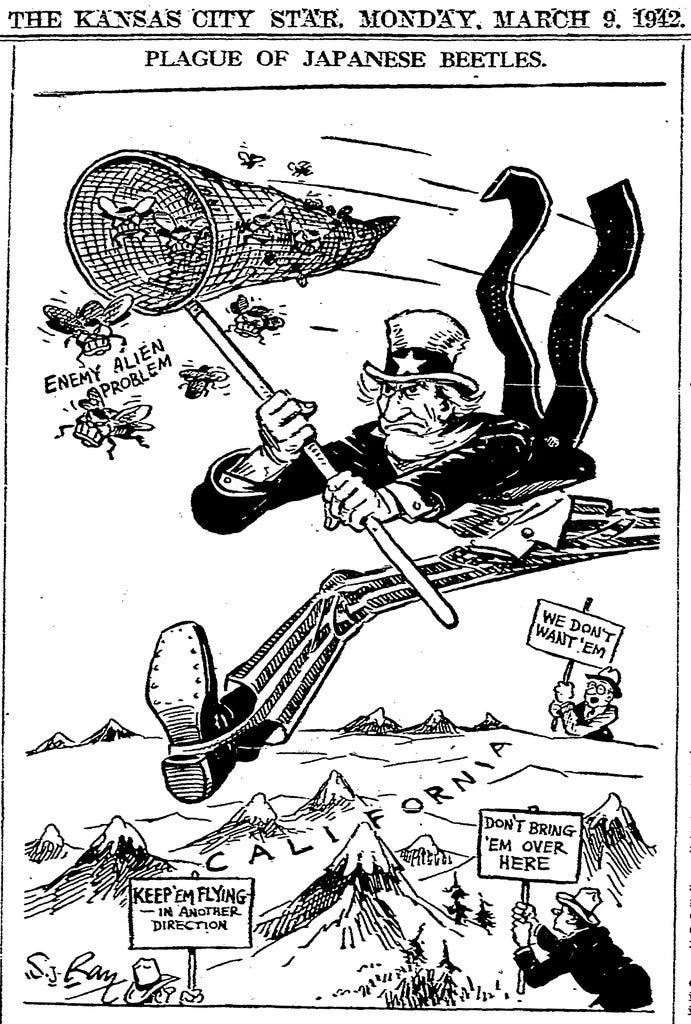

December 7, 1941, changed everything. The attack on Pearl Harbor ignited a nationwide panic, fueling rumors of sabotage by anyone of Japanese descent. Newspapers, radio broadcasts, and propaganda posters warned of an “invisible enemy”—and the racial caricaturing was relentless.

Even Dr Seuss drew anti-Japanese cartoons, depicting Japanese Americans as treacherous traitors.

Fears of Japanese Americans collaborating with their homeland were echoed in newspaper editorials and cartoons across the country.

Following the shock of Pearl Harbor, a wave of suspicion descended onto Japanese American communities. First the federal government came for community leaders - priests, heads of local associations, family men who suddenly found themselves “enemy aliens.”

Hysteria soared so high that rumors spread of “traitorous” Japanese Americans posing as Chinese—then a U.S. ally—just to dodge arrest.

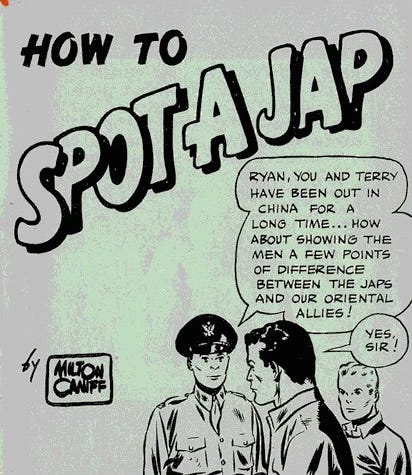

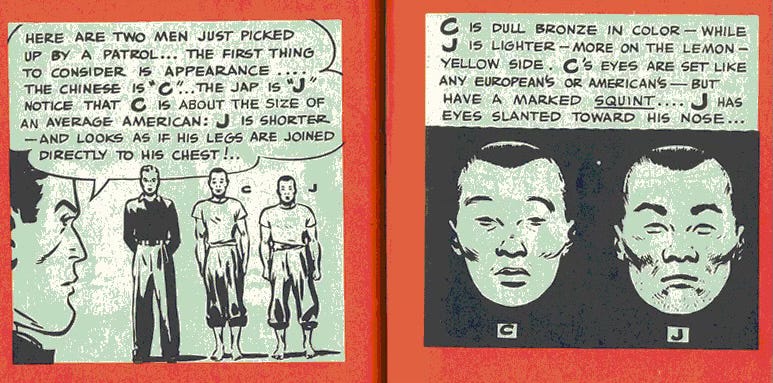

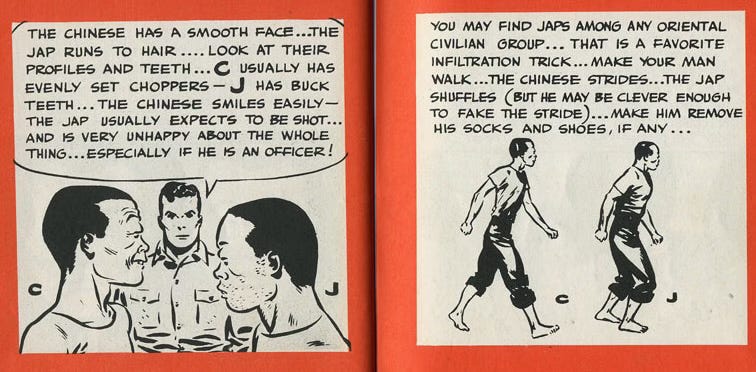

To illustrate the extend of the fear, here’s a few pages from “U.S. Army’s Pocket Guide to China” illustrated by Milton Caniff (who later created Steve Canyon).

Crude caricatures were used to identify “friend” from “foe,” revealing a disturbing reliance on visual profiling even in official wartime publications. ~ Source

The rapid intensification of hostility toward Japanese Americans set the stage for mass government action—an overreaction that would uproot tens of thousands of innocent people.

Executive Order 9066 and the Roundup

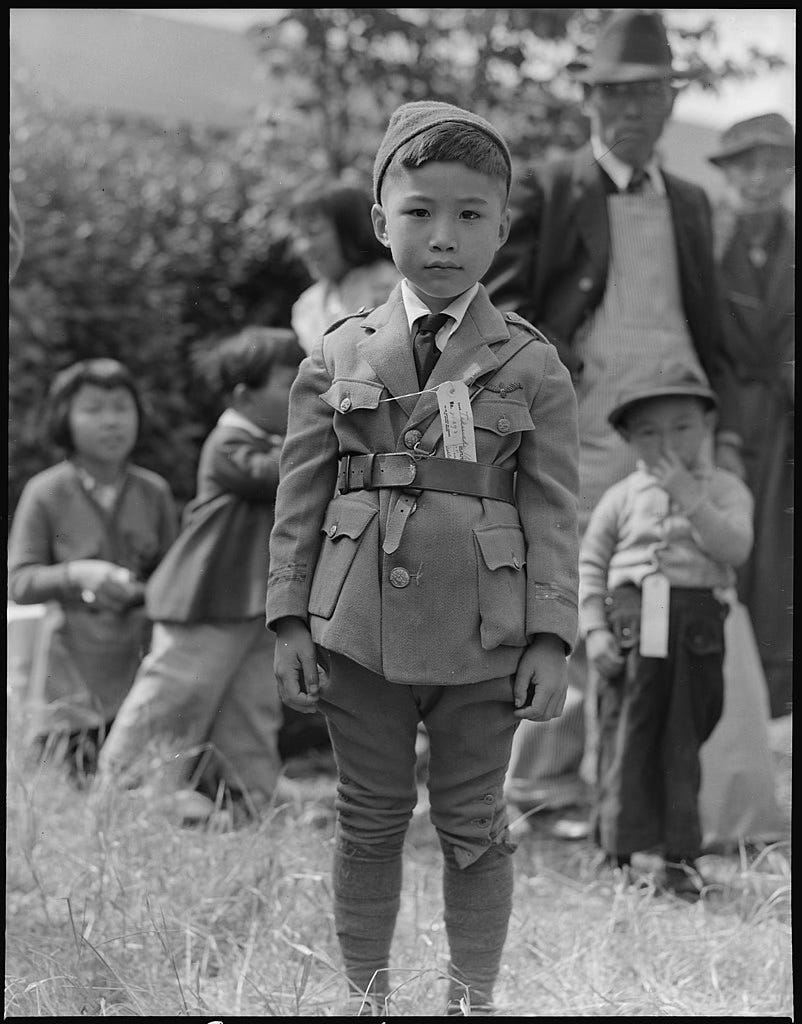

In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, granting the military sweeping authority to force anyone of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. A handful tried “voluntary evacuation,” but the vast majority had no choice but to report to makeshift “assembly centers” in fairgrounds and racetracks.

As families boarded crowded trains, often with only a week’s notice, they left behind fields ready to harvest, businesses, and neighborhoods they had built—stepping into a future as uncertain as it was unjust.

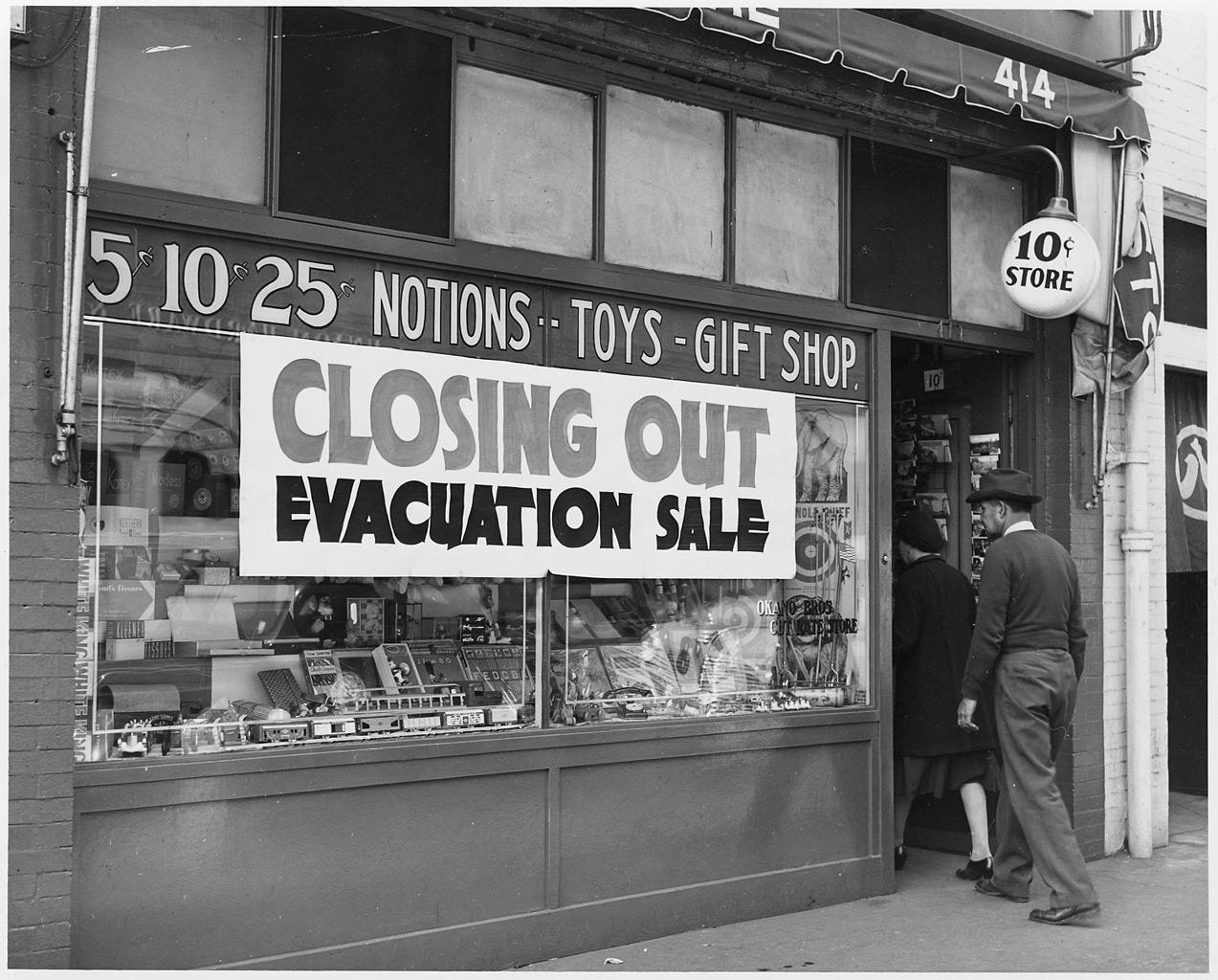

Families had days—sometimes mere hours—to pack what they could carry. Whole communities were shattered overnight, entire blocks stripped bare as anxious shopkeepers boarded up storefronts and farmers walked away from crops nearly ready for harvest.

Because Japanese immigrants were prohibited by law from owning property, many rented farmland, hotels, and retail spaces. But the hasty roundup left them no chance to secure livelihoods or salvage what they had built. They boarded crowded trains to makeshift “assembly centers” in fairgrounds or racetracks—with little idea of what lay ahead.

Over 110,000 men, women, and children—most of them American citizens—were uprooted and incarcerated without charge, condemned solely for their ancestry. A once-thriving tapestry of neighborhoods and businesses became vacant and silent, a stark reminder of injustice directed at an entire community that had committed no crime.

Homes sat vacant or were seized; small shops shuttered as frightened owners liquidated goods in “evacuation sales.” In cities on the west coast, whole blocks of Japantowns were emptied, turning once-bustling streets into ghostly rows of boarded-up storefronts.

Remote Concentration Camps

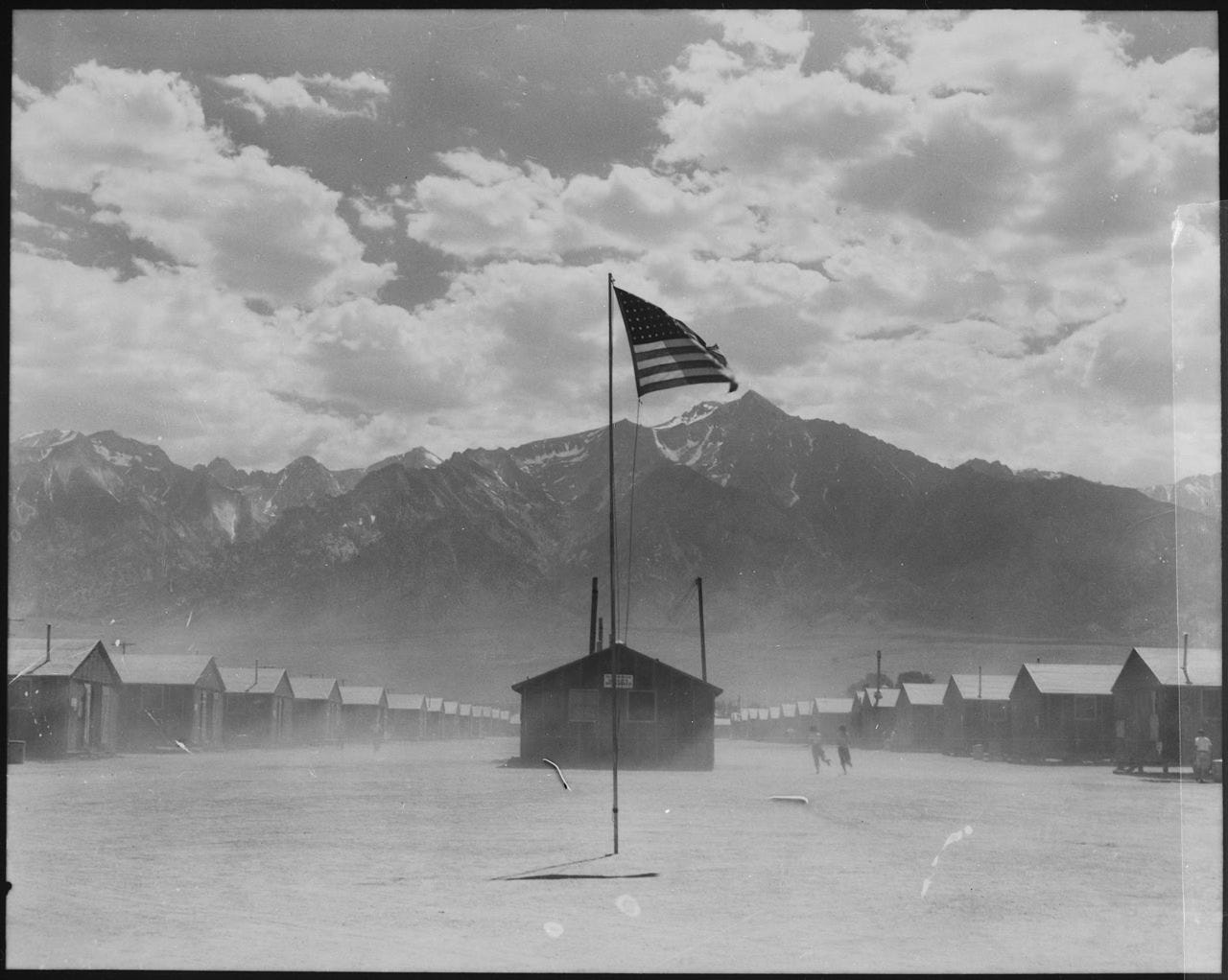

At first the government relied on temporary “assembly centers” near urban centers. But before long, it established makeshift “relocation centers” in desolate spots far from the west coast—Manzanar, Minidoka, Tule Lake, and others—surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by armed soldiers.

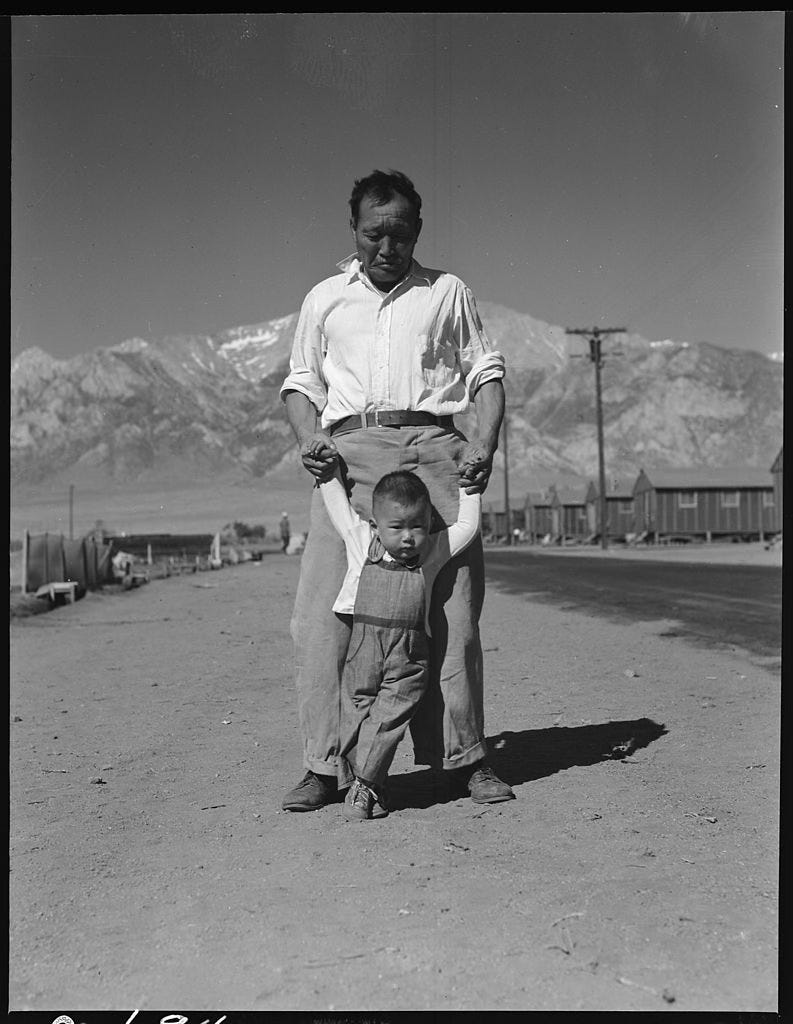

In these crude camps families lived in cramped barracks, often with limited privacy and harsh weather conditions. Children attended rudimentary schools; adults tried to maintain routines, organizing community meals, churches, and even baseball leagues. But underlying it all was the pain of confinement, stripped of rights and possessions.

Back home, the losses were staggering—their farms vandalized, their businesses ruined, and their property sold off at auction. The material damage was enormous, but the psychological and generational toll was worse.

Aftermath of Incarceration

When the concentration camps finally closed, most Japanese Americans were released with little more than a bus ticket and a few dollars. Returning to their old neighborhoods often meant discovering vandalized homes or finding their businesses taken over. In many cases, even former friends and neighbors kept them at arm’s length, convinced by years of wartime propaganda that Japanese Americans remained a threat. Others had nowhere at all to return to, their possessions sold for pennies or stolen while they were behind barbed wire.

Despite these staggering losses and persistent hostility, Japanese Americans demonstrated remarkable resilience. Many rented new spaces or moved to unfamiliar cities where they painstakingly rebuilt their lives from the ground up. Parents worked multiple jobs to send their children to college, and communities banded together, offering mutual support through newly formed cultural or religious organizations. It would be decades before the U.S. government offered a formal apology and financial redress. By then, countless survivors had already forged fresh starts, quietly shouldering trauma and loss that would echo through generations.

Lessons Learned?

We’ve been here before: during World War II, it was Japanese Americans—ripped from their homes and locked in camps without a fair hearing. Today, it’s Venezuelan migrants, cast as “alien enemies” under a centuries-old law that only applies when the nation is at war—yet we’re not at war.

These migrants were already in custody. They weren’t seeking release—only protection from removal under the Alien Enemies Act. … And this is a wartime law, and we are not at war with Venezuela. No court has weighed their cases; no judge has considered evidence or guilt.

Instead, in a chilling echo of past injustice, they’re shipped off to foreign prisons under the same twisted logic that once allowed barbed wire to encircle innocent families on American soil.

This isn’t about whether someone is “guilty” or “innocent.” It’s about a government willing to shred constitutional protections by branding an entire community as a threat. Just as Japanese Americans once found themselves demonized overnight, The administration now targets immigrants and foreign visitors with sweeping labels and fear-mongering.

We claimed we learned from our past—that we’d never again shame our principles by jailing people without due process. Yet the very law that fueled mass incarceration in 1942 is back on the table, used not for national defense but as a weapon against the most vulnerable.

Let this dark parallel serve as a warning: if we once believed we could betray our own values in the name of “security” and simply move on, history is now shouting for us to think again.

Explore Portland’s Historic Japantown in my Award-Winning Interactive eBook

My University of Portland students and I partnered with the Japanese American Museum of Oregon to document the history of Portland’s Japantown.

From that collaboration came a free, interactive digital book—complete with videos, interviews, photo galleries, and primary-source documents—that lets you explore this vibrant community in a whole new way.

One of its best features are its interactive “reveal” images. I took contemporary photographs at the exact locations shown in historical photos, then carefully overlaid them.

You can “paint” the past right into the present, bringing historical figures and scenes to life. Move your cursor over the contemporary photo and reveal the 1917 Japanese Baths and the family that owned it.

“Portland’s Japantown Revealed” is available exclusively on Apple devices (Mac, iPad, or iPhone). It’s easy to download, fun to navigate, and best of all, completely free. Don’t miss this chance to immerse yourself in a fascinating chapter of local and national history.

Download “Portland’s Japantown Revealed” on Apple Books and step into Portland’s past today

Reading this made me sick to my stomach and overwhelmingly sad. We are watching history repeat itself. The administration is so very arrogant with its America First agenda that makes me embarrassed. We are the richest country in the world and we're forgetting that our country was founded on immigrants. How sad and disgusting it is to hear Stephen Miller spout lies to everyone just because he feels better than everyone else. Just sickening.

The propaganda campaign to malign Japanese was so affective that my mother continued to fear Japanese people for many decades. She was a high school student in California during the war and had powerful memories implanted by the anti-Japanese sentiments of the time. Over 50 years after the war ended, I shared with her my interest in applying to work/teach English in Japan and she was quite worried and tried to talk me out of it. Her pleas for me to not go were shocking as she was otherwise a very kind and compassionate person.

I think the lesson here is, YES! it is very important that we speak up against the actions and messaging of the current administration. Not only might this help those detained illegally but it may also help counteract the unnecessary/unjustified fear and prejudice influenced by the government’s actions.