Doomsday in the Suburbs

When Fallout Shelters Took Over America

In the early 1960s, America was gripped by the fear of nuclear war, and nowhere was this more evident than in the fallout shelter craze that swept the nation during John F. Kennedy’s presidency. What started as a government push for civil defense quickly turned into a booming business, where fear was transformed into profit, and survival became a hot commodity.

In 1961, President Kennedy sparked shelter mania when he stated in a “Life” magazine cover story that 97% of Americans could survive a nuclear attack if they retreated to a well-stocked fallout shelter.

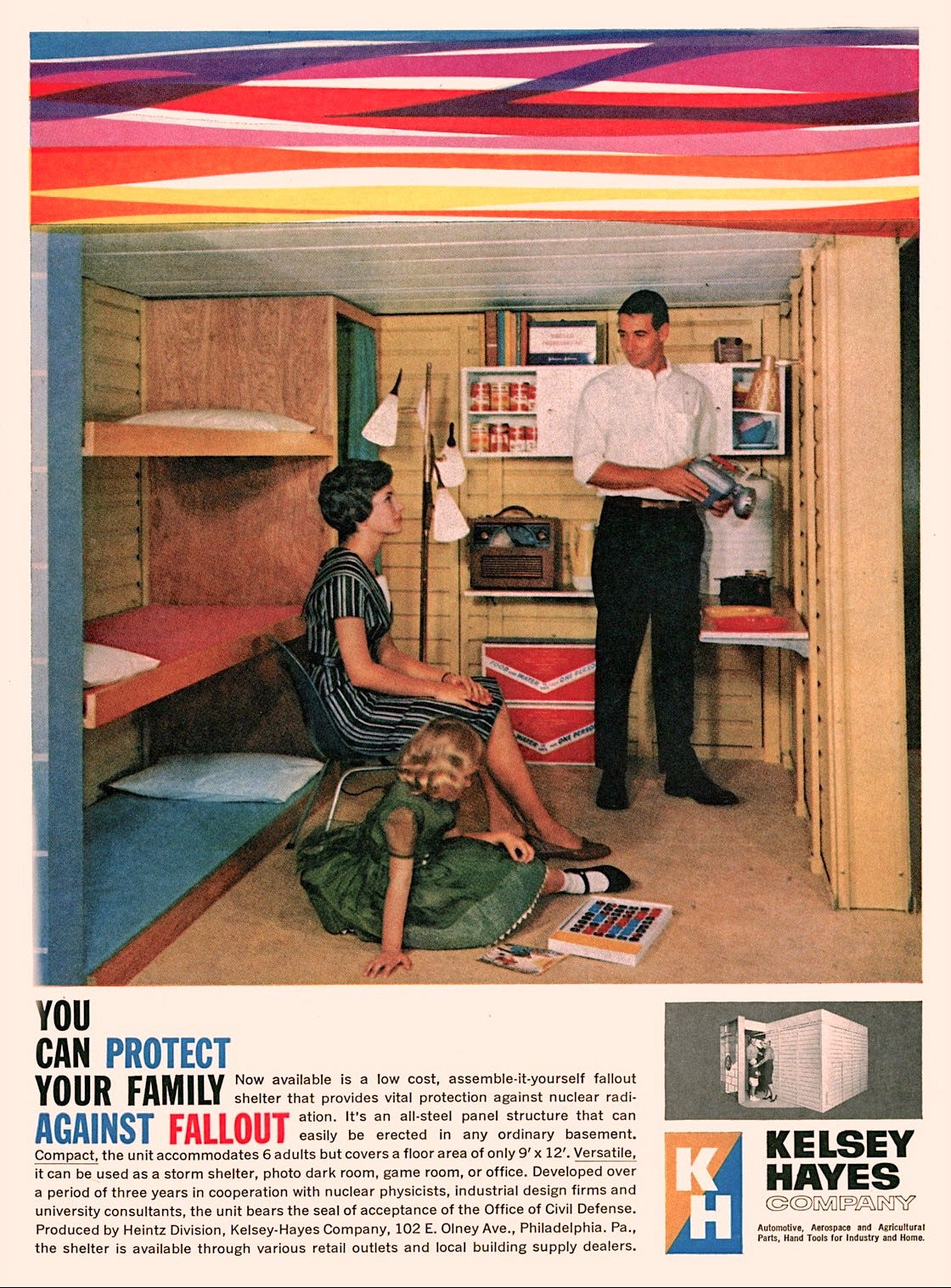

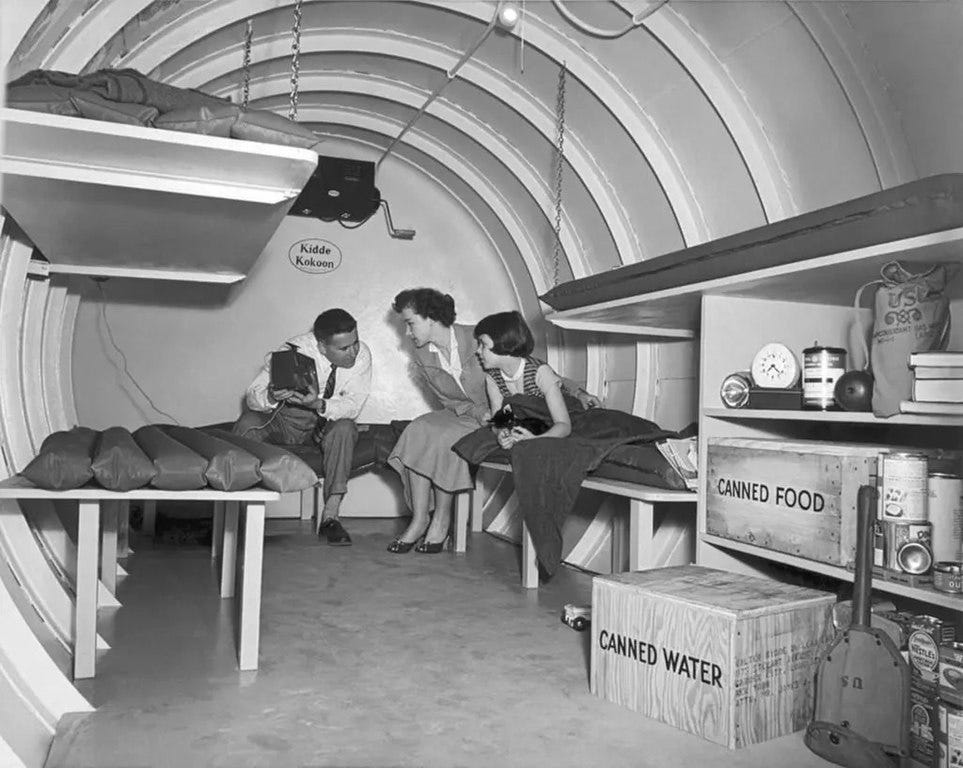

With Kennedy’s endorsement, the fallout shelter industry took off like never before. Companies like Kelsey Hayes, for example, a wheel and brake manufacturer pivoted to producing fallout shelters. These weren’t just any shelters—they were marketed as must-have extensions of the American home, complete with air filtration systems and stocked pantries.

Advertisements played heavily on the fear of nuclear war, urging Americans to protect their families by investing in their own personal bunkers. “Protecting Your Family” was a common theme, appealing to both the head and the heart. And just below the surface lurked the reality of our class divides - not everyone could afford a fallout shelter.

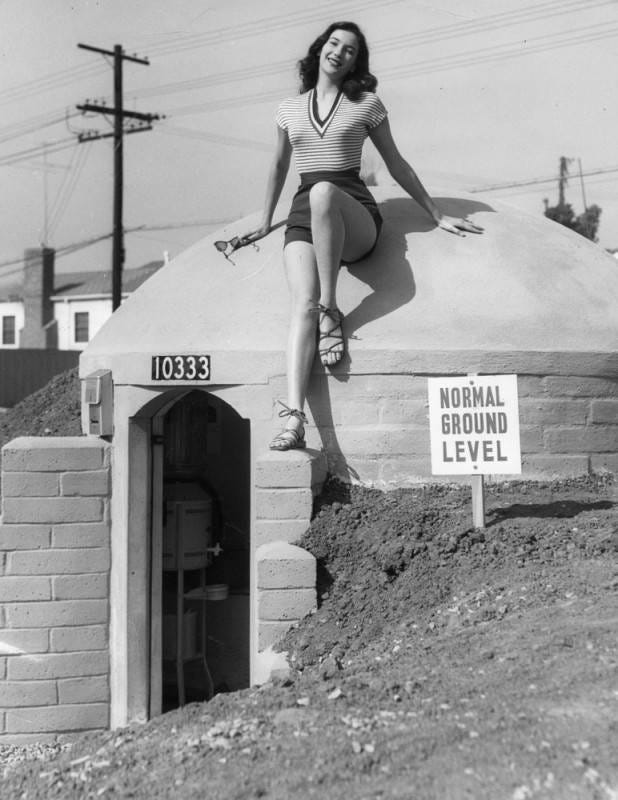

This wasn’t just about survival—it was about status. Owning a fallout shelter became a symbol of preparedness, a badge of affluence and responsible citizenship in an uncertain world.

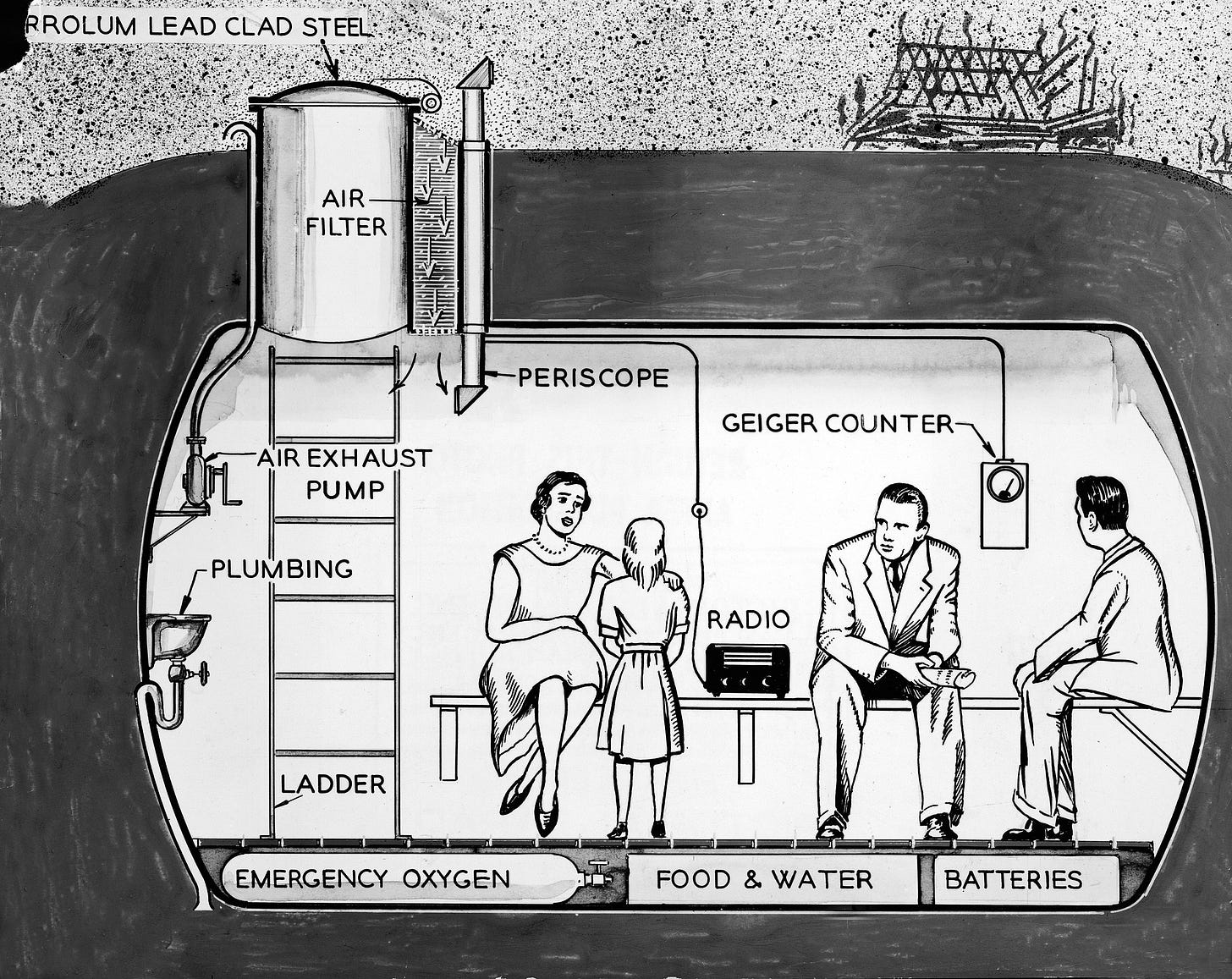

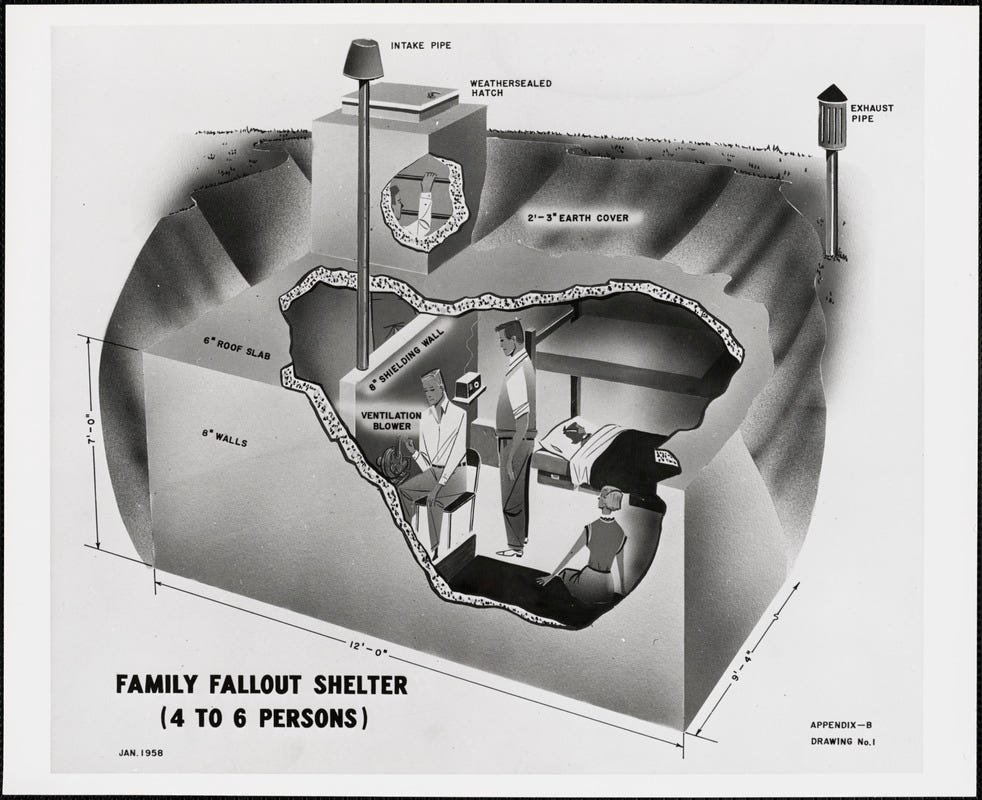

The economic ripple effect was enormous. Home improvement stores saw a surge as families scrambled to retrofit their basements or backyards, guided by government-issued blueprints that made DIY shelters seem both practical and patriotic. The fallout shelter industry didn’t just thrive—it exploded, turning Cold War anxiety into cold, hard cash.

These shelters were designed to blend seamlessly into the suburban landscape, hidden in basements or disguised as garden sheds. The goal was to be prepared without alarming the neighbors—discreet yet effective.

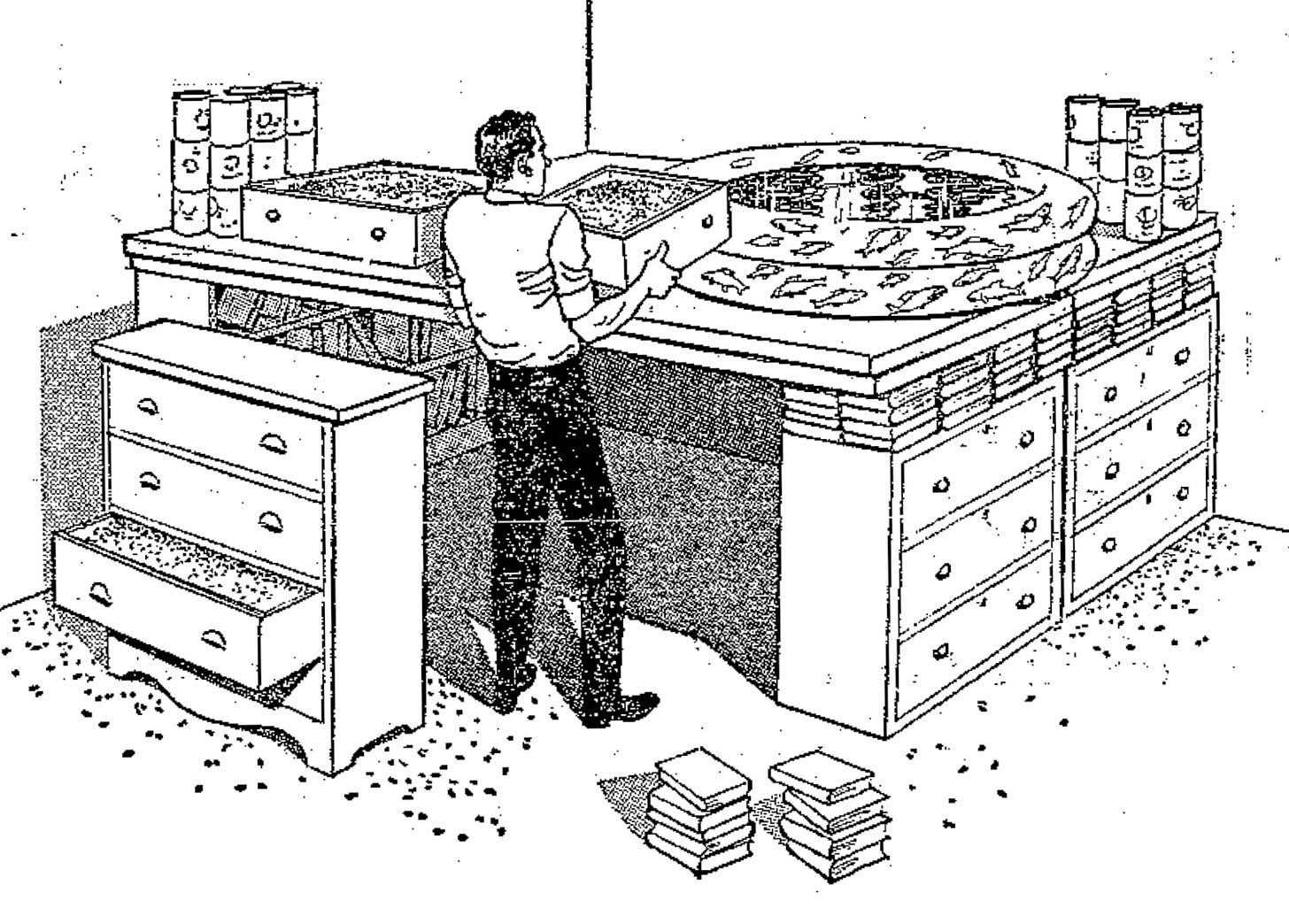

For those without the money or space to build a proper fallout shelter, the government’s improvised solutions were almost laughable. Civil defense booklets advised using doors, sand-filled dressers, stacks of books, and even a kiddie pool filled with water to create makeshift bunkers.

These absurd DIY shelters starkly highlighted the class divide—while some families had fully-equipped underground havens, others were left piling up furniture in a desperate attempt to shield themselves from the unimaginable.

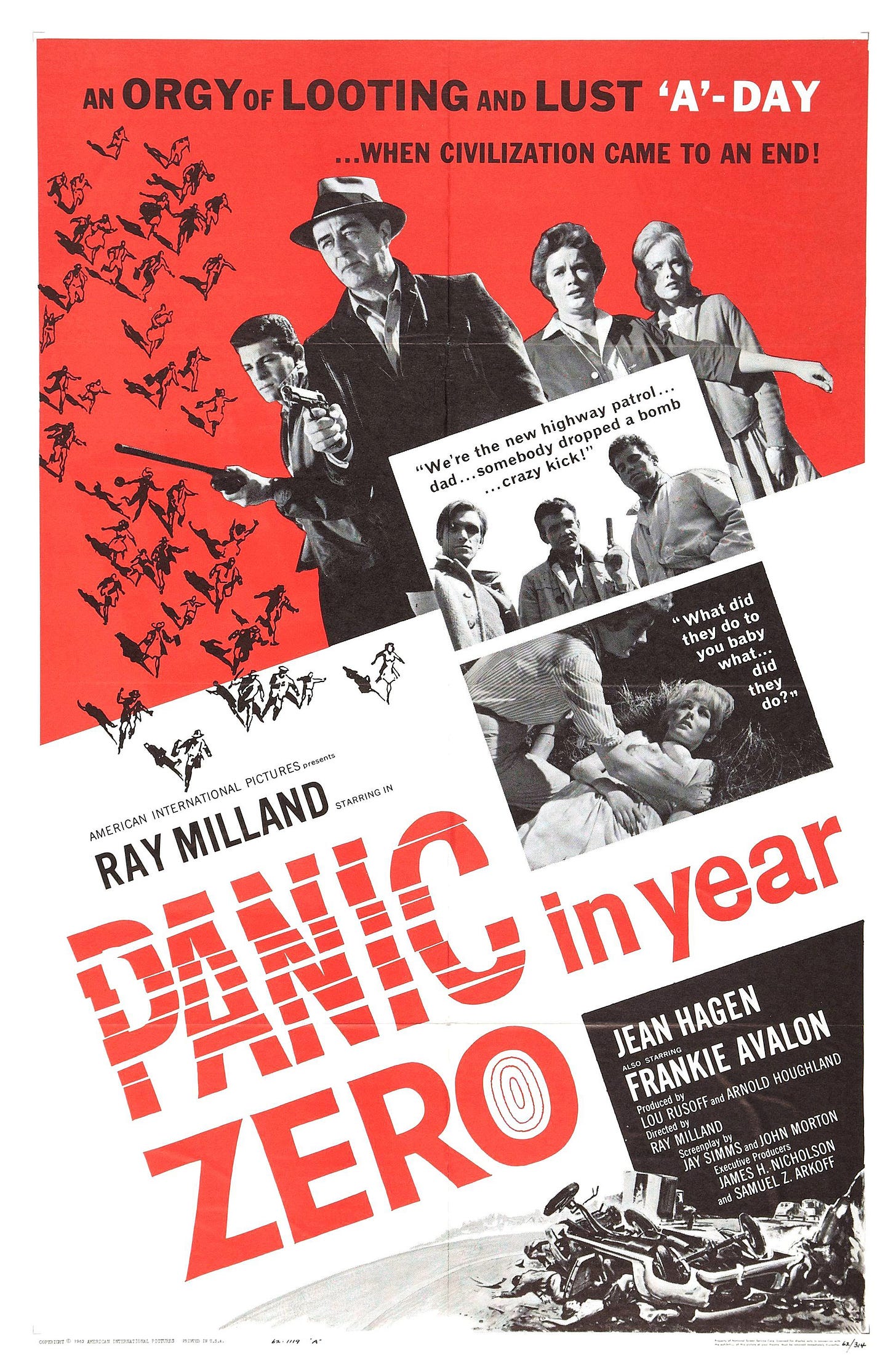

The fallout shelter craze didn’t just fuel an economic boom—it left a deep imprint on American culture. Films like “Panic in Year Zero!” explored the dark side of survival, mixing horror with humor.

Despite the government’s best efforts, not everyone bought into the fallout shelter craze. Critics like philosopher Bertrand Russell argued that it promoted a selfish, futile form of survivalism. As the initial panic of the Cuban Missile Crisis faded, so too did the shelter obsession, leaving behind empty bunkers and a sense of collective relief.

Cartoons in MAD Magazine and The New Yorker mocked the idea of fallout shelters as grim, claustrophobic spaces where the illusion of safety was shattered by harsh reality.

Songs like Tom Lehrer’s ‘We Will All Go Together When We Go’ satirized the grim irony of surviving a nuclear blast only to confront a desolate and uninhabitable world.

Imagine it: a family of four crammed into a concrete box no bigger than a 8’ X 12’ shed, subsisting on canned beans and powdered milk, all while the world outside has gone up in radioactive smoke. The kids bicker over who gets the top bunk, Dad fiddles with the air filter like it’s a lifeline, and Mom tries to keep morale high with stories of better days ahead—if they ever make it out.

But let’s be honest, the real absurdity isn’t just the claustrophobic confines or the canned food diet. It’s the idea that after weeks—or even months—of living in this subterranean purgatory, they’d emerge to a world so devastated, it would make the shelter look like a luxury hotel.

The marketing promised safety and survival, but they conveniently skipped over the small detail that what awaited outside might make them wish they’d never left the bunker in the first place.

In the end, the home fallout shelter was as much a psychological comfort blanket as it was a survival tool. Sure, it might shield a family from the initial blast, but what then?

Living in a cramped, concrete box for weeks or months, only to emerge into a world so ravaged that the idea of rebuilding anything resembling normal life seems laughable. It’s hard not to see the absurdity in it—especially when you realize that the real threat wasn’t just the bomb, but the world it would leave behind.

Today’s tech moguls planning their escape to Mars feel eerily similar. Just as families in the 60s imagined surviving nuclear war in their basements, today’s billionaires dream of thriving on a barren, hostile planet.

But much like the fallout shelters, life on Mars could offer little more than a hollow survival in a desolate, unyielding environment. Instead of banking on escape plans—whether to a fallout shelter or a distant planet—it’s time to focus on fixing the problems we have here, so we never need to hide underground or flee to the stars.

More Cold War?

Reagan's World Revisited (1982)

These two satirical representations of the world from the perspective of Ronald Reagan were created by David Horsey, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist and columnist.

I was an eighth grader during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and I remember JFK explaining the range of the Russian missiles in Cuba. (Yes, they could reach me in Rochester NY). Not long afterwards, "Saturday Night at the Movies" featured the Gregory Peck film: "On the Beach" which depicted the last days on earth after an atomic war.

I begged my parents to put in a fallout shelter (we never did). Although I did come up with plans to quickly build an improvised shelter under a heavy workbench in the basement. Fun fact: I still have a fallout shelter flyer I saved from back then.

I was in elementary school in Calgary when the Cuban missile crisis happened. We had a few civil defence drills because Calgary had a NATO base, so it was considered a secondary target. I don't recall anyone building fallout shelters though. I guess that was mostly an American thing. The bizarre part of those drills was that we were sent home from school when the air raid sirens went off! I guess they figured better to die at home with your family than cowering in the school basement, but seriously, what were they thinking? At least we didn't have to duck and cover...lol.

I recall reading somewhere that the true intent of the fallout shelter craze was not to survive a nuclear war, but to convince the Soviet Union that the US government was able to convince the population that it was actually possible to survive a nuclear war - sort of an early psyop. The USSR of course had entire subway systems dedicated to the idea, which is why the Moscow metro is so far underground.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8t5QKYa248

Along the same lines, people often comment on the width of Russian boulevards as if city planners had in mind an open and pleasant environment. Quite the contrary. Those boulevards were intended to make invading tanks easy targets from the surrounding buildings, which themselves had bunkers and connecting tunnels so fire teams could move between them without risk of exposure. If you look at the recent battle of Mariupol that's one of the reasons it was so difficult. Not only are the apartment blocks connected with tunnels, but the buildings themselves are arranged as fire positions, so no single building can offer cover - you are always in the fire line of one building or another.